10 Fairey Swordfish

Designed during the 1930s, the Fairey Swordfish was a biplane torpedo bomber. Although the Swordfish was state of the art at the time of production, monoplane fighters and bombers soon made biplanes look obsolete. The Swordfish used World War I ideas. It had a large, open, three-seat cockpit and a rudimentary defensive armament. By the time that World War II began, the Air Ministry believed that Swordfish squadrons would get torn apart and began designing a new torpedo bomber. However, the new planes were not arriving fast enough for the navy. They continued to use the Swordfish for operations until they got new airplanes. In combat, however, the Swordfish quickly distinguished itself. In 1940, the HMS Illustrious conducted an attack against the Italian navy at Taranto using Swordfish bombers. During the attack, these planes knocked out a good chunk of the Italian navy. A year later, the Royal Navy used a Swordfish to attack the German battleship Bismarck. The giant ship was a menace to the British Navy. But after the navy spent months trying to sink the Bismarck, a Swordfish struck the key blow. A torpedo launched from a Swordfish damaged the rudder of the Bismarck, forcing it to sail in circles while British surface ships closed in for the kill. During the war, the Swordfish distinguished itself as an effective fighting machine. Fairey built the Albacore torpedo bomber to replace the Swordfish, but the new plane was ultimately disappointing. The Air Ministry retired the Albacore before the Swordfish, allowing the ungainly biplane bomber to outlive its intended replacement. Various modifications improved the bomber, including the use of small rocket engines to lift heavy-laden planes off carrier decks. When the end of the war rolled around, the Swordfish was still in service, an impressive feat for an old biplane in the age of jet engines.

9 Vickers Machine Gun

Another outdated British weapon from World War II was the Vickers machine gun. When the war started, the Germans used the excellent MG 34 and MG 42 machine guns. These weapons came into service right before the war or during it. On the other hand, the British entered the war with the Vickers, an archaic machine gun designed in the early 20th century with late 19th-century technology. Unlike more modern machine guns, the Vickers was water-cooled. Vickers based their design on the Maxim machine gun, which was created in the late 1800s. Basically, they took the design and made it lighter and more efficient. To prevent overheating, the gun used a water pump to cool the barrel. During World War I, the Vickers was the main machine gun of the British armed forces. Surprisingly, they were still using the same gun 25 years later in World War II. British infantry used mass firing tactics to soften up German defenses and take advantage of the Vickers’ firing rate. In combat, the gun was absurdly dependable in all environments. Modified Vickers were used on airplanes and surface ships. The designed stayed in service throughout the war and beyond. British forces used the Vickers through the 1960s, when the guns were finally replaced by more modern weapons. Not bad for a machine gun designed in the 19th century.

8 The Bayonet Charge Of The Argyll And Sutherland Highlanders

In the age of computerized technology and unmanned weapon systems, it seems archaic that soldiers are still trained to use bayonets, a holdover from earlier centuries of fighting. Although the average soldier may never use his or her bayonet in combat, an Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders detachment conducted a bayonet charge during the Iraq War, one of the few examples of this strategy in the modern era. During an extraction mission in 2004, the detachment found themselves surrounded by Iraqi forces. Unable to find a quick way out of the situation, the commander of the detachment ordered his men to fix bayonets, the first time since the Falklands War that a United Kingdom commander had issued this order. Getting their bayonets ready, the Highlanders charged the enemy position, capturing it and forcing the Iraqi forces to retreat. Part of the success of the charge came from its unexpected nature. During the invasion, Iraqi forces had spread propaganda that the Allied forces were weak and cowardly. Scots charging with bayonets soon proved the propaganda wrong.

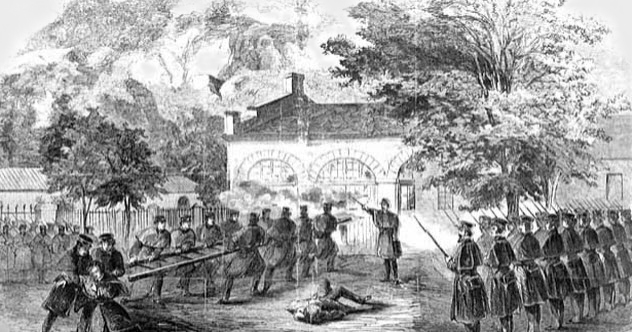

7 Harpers Ferry Pikes

Pikes were the mainstay of infantry before gunpowder. But as guns became more effective in Europe, the need for pikes gradually disappeared in the 17th century. Like many archaic weapons, the pike made a brief comeback during an unexpected event—John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry. In the lead-up to the US Civil War, John Brown was increasingly angered by slavery. Believing that peaceful abolitionists were moving too slowly, Brown decided to take things into his own hands. In 1857, he planned to take over the arsenal at Harpers Ferry to incite a slave revolt. While trying to raise support on the East Coast, Brown contacted blacksmith Charles Blair of Collinsville, Connecticut. Brown wanted Blair to build weapons for him, including 500 pikes. When Brown returned for his pikes, he did not have enough money to pay for them. So Blair kept the pikes in storage for two years. In 1859, Brown showed up and demanded 500 more of the weapons plus the ones already produced. This time, he had enough money to pay for the archaic pikes. Soon after, Brown launched his attack on Harpers Ferry. A few of his soldiers used the fearsome pikes, which were 2 meters (7 ft) long. But most were kept in storage for the eventual slave uprising. Brown’s attack failed, and he was hanged for treason. Souvenir hunters snatched up the leftover pikes. Many still exist, an odd reminder of a bygone era.

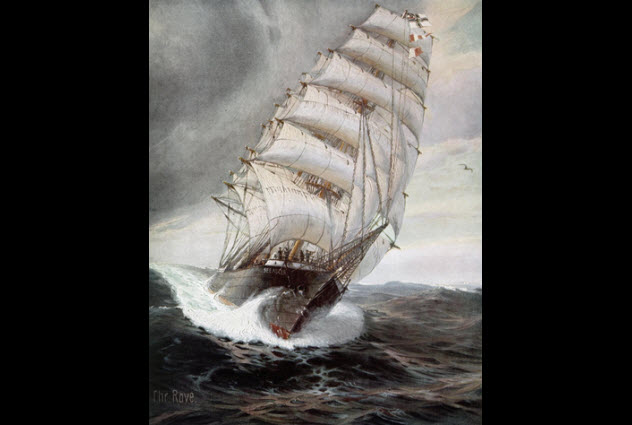

6 SMS Seeadler

Built in 1888, the SMS Seeadler was first named the Pass of Balmaha. She was a three-mast sailing ship designed as a transport ship. During a trip from New York to Arkhangelsk, Russia, a British auxiliary cruiser intercepted the ship. The cruiser’s captain believed that the Pass of Balmaha had contraband material on board and ordered them to divert course to Kirkwall in the Orkney Islands. Within a few days of leaving the cruiser, the Pass of Balmaha ran across the U-36, a German submarine. The German crew was less understanding and took the ship and crew prisoner. Although the American crew returned to a neutral country, the ship became part of the German navy. Renamed the SMS Seeadler, the ship became a commerce raider with two 105 mm guns on the deck and an auxiliary diesel engine to augment the sails. The new ship took to the seas in 1916. Captain Felix von Luckner disguised the ship as a Norwegian vessel, which allowed him to make his way past the British blockade and into the Atlantic. The old sailship ended up capturing or sinking 16 ships during its short career on the high seas. Quickly, the French and British sent out ships to sink the Seeadler. After being chased for a long time, the Seeadler struck a reef in Tahiti. Although damaged, the crew attacked one more ship before grounding at Easter Island. The Chilean government captured the crew and interned them for the rest of the war, thus ending the career of one of the last combat sailships.

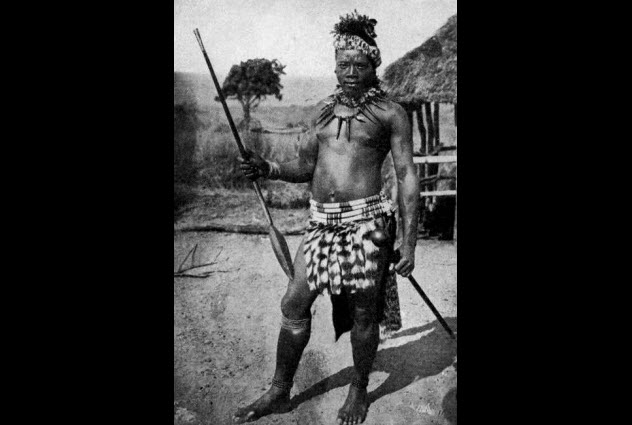

5 Zulu Ikwla

In the late 19th century, the British Empire fought in South Africa to unify the southern part of Africa under British rule. In 1879, the British began a military campaign against the independent Zulu kingdom with annexation as the ultimate goal. The British assumed that the war would be an easy campaign because the Zulus weren’t using modern weapons. The two major Zulu weapons were older melee weapons. One was a long spear called the assegai. The other was the ikwla. This was a short version of the assegai and was the main weapon of the Zulu warriors. Named after the sound that it made when pulled from the body of an enemy, the ikwla was deadly in the hands of a trained warrior. Zulu training centered on effective use of the blade because a warrior who lost his ikwla in battle was considered to be a coward. The British severely underestimated the discipline required to use the ikwla. Lieutenant General Lord Chelmsford began the invasion of Zululand in January 1879. Chelmsford divided his forces into three columns and headed toward Isandlwana Hill. Unknown to British forces, the Zulus had mobilized 24,000 warriors to attack the 2,000 invaders. Armed with hand weapons, the Zulus prepared their attack and were spotted by British reconnaissance troops. Although the British camp was warned quickly of the impending attack, it was too late. Zulu warriors descended on the British troops in a three-pronged attack. At first, the British soldiers were successful, firing volley after volley into the Zulus. However, their ammunition ran out quickly and resupply logistics fell apart. Deprived of long-range weaponry, the British fought hand to hand with the Zulu warriors and their ikwla. Facing warriors who had trained extensively for hand to hand combat, the British forces were decimated. In the end, 900 British soldiers lay dead, mostly from ikwla wounds. The battle was a decisive Zulu victory and held off the British invasion force for a few months. Eventually, the British annexed Zululand successfully, but the Battle of Isandlwana remains a fascinating story of native forces defeating colonial interests. In this case, old weapons defeated the modern ones.

4 British World War II Carrier Pigeons

Militaries used carrier pigeons during the 19th century and World War I. By the time World War II started, most strategists thought that military pigeons were useless. But as the war began, the British realized that birds were still an important part of military communications. To that end, the British trained over 200,000 pigeons for wartime use. The other side used pigeons, too, but not to the extent that the British did. Pigeons were used for auxiliary communication when normal radio communication was impossible or there was a high likelihood that Axis forces could intercept the transmissions. Throughout the war, the British used their pigeons to cross enemy lines and deliver secret orders or coded messages about troop positions. These birds usually had fun names like Lady Astor, Pepperhead, or Holy Ghost. As the pigeons were such an important part of communications, the British invented the bronze Dickin Medal for them and other animals that accomplished brave tasks. One pigeon named Winkie won the medal for flying 200 kilometers (120 mi) to a downed bomber crew and then back to base. Knowing the time that the bird was aloft, the Royal Air Force was able to calculate the downed crew’s position and rescue them. Another pigeon named William of Orange won a Dickin Medal for delivering a critical message in record time during the Battle of Arnhem.

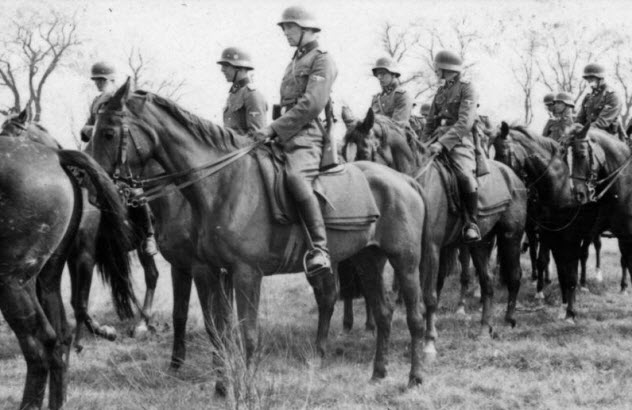

3 Wehrmacht Horses

Today, most people believe that the German army relied purely on mechanized might to crush its enemies during World War II. However, the reality was far different. While the Germans did use some of the most advanced weapons of the war, they were also practitioners of old technology and tactics, especially the use of horses in military logistics. In a war with nuclear bombs and heavy tanks, the use of horses seems quaint and outdated. But they were oddly effective. Throughout the war, the Germans deployed close to 1.1 million horses at a time, much larger than their tank divisions. Most of the horses transported baggage and artillery cannons because armored vehicles were in short supply throughout the war. The Germans also used mounted cavalry to navigate difficult terrains and conduct flanking attacks. Even groups like the feared SS used horses during their operations, most notably during battles on the Eastern Front. By the time the war ended, the Germans were using cavalry to cover retreats. Since Allied bombing had eliminated most fuel production plants, horses were the best means of transportation. The Allies did not waste bombs on horse farms.

2 Polikarpov Po-2

First flown in 1927, the Polikarpov Po-2 was similar to the biplanes of World War I. However, despite being slow and weakly armed, it became an extremely successful airplane in World War II and the Korean War. The Soviet Air Force pressed Po-2 biplanes into service to fight against German attackers. Since the airplane would get torn apart during daylight operations, the Po-2s mainly conducted night raids. During the attacks, the pilots took advantage of the Po-2’s excellent gliding capabilities. Before they reached their target areas, the pilots turned off their engines and glided over the targets silently. The Po-2 was so slow that it was nearly impossible to intercept. That’s because the biplane’s top speed was lower than the stall speed on German fighter planes. The most famous of the Po-2 squadrons was the 588th Night Bomber Regiment, an all-women group of Soviet aviators who conducted such effective ground strikes that they earned the nickname “night witches.” After World War II, the Soviet Union phased out the biplanes. But North Korea kept using the Po-2 as the Soviets once had. Nicknamed “Bedcheck Charlies,” North Korean Po-2s conducted late-night raids against UN air bases. Jet fighters had the same stalling problems that the German fighter pilots once had, which made intercepting the Po-2 extremely difficult. Beyond that, the wooden and fabric airframe was nearly impossible to pick up on radar. The Po-2 is the only biplane to document a jet kill. A Po-2 pilot tricked an American F-94 pilot into slowing down below stall speed, causing the jet to crash.

1 Jack Churchill’s Longbow

While World War II dragged on with its technological advancements, British army officer Jack Churchill remained rooted in the ideas of the past. Famously saying that “any officer who goes into action without his sword is improperly dressed,” Churchill charged into battle with a large sword and a longbow. Other nations and soldiers used swords during the war, but Churchill remains unique in his use of the longbow. Churchill fought from 1940 until the end of the war and spent most of his time in British Commando units. During his combat actions, Churchill used the longbow to signal an attack or charge for his men. In 1940, Churchill killed a Nazi NCO in France with his longbow. Scholars consider this to be the last confirmed kill with a longbow in history. Even though Churchill didn’t kill anybody else with the longbow, his use of the weapon became iconic. He developed a reputation for invincibility on the field, leading to various outlandish victories. The most notable one occurred at the town of Piegoletti. While screaming and charging through the night with his medieval weapons, Churchill led his troops to victory against a superior Nazi force. Churchill’s use of the longbow is best described by British weapons historian Mike Loades: Shooting someone with a longbow as the overture to opening up with rifles doesn’t suggest a specific advantage for using the longbow in that situation, but rather a macabre curiosity of using the situation to see what it was like to kill someone with a longbow. Zachery Brasier (despite being relatively antiwar) likes writing about military history.