10Bigots Against Slavery

Northern abolitionists, who angrily demanded justice and equality for African Americans in the South, could be a lot less progressive when it came to the women in their own homes. There was a common belief that women were intended to be wives and mothers subservient to their husbands. So it was fine when thousands of women worked to end slavery by handing out pamphlets or signing petitions, but it was considered unacceptable when they started to lecture or tried to become leaders. Two white sisters from the South, Sarah Moore and Angelina Grimke, joined the lecture circuit to share their eyewitness accounts of the horrors of slavery. In 1836, when the sisters spoke to mixed audiences of both men and women, it was considered so unladylike that many shocked anti-slavery activists tried to silence them. Another example of gender discrimination came in 1840 at the World Anti-Slavery Conference in London. Male abolitionists seated the elected female delegates off to the side and wouldn’t let them address the male delegates. Soon, some female abolitionists decided that they couldn’t effectively help slaves gain freedom that they themselves didn’t have. In 1848, Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton—two of the abolitionists who’d been sidelined at the London conference—took center stage in Seneca Falls, New York, where they held America’s first women’s rights convention. Stanton introduced “The Declaration of Sentiments,” a list of resolutions on women’s rights—including the resolution that women should be able to vote. Though the ideas promoted at the Seneca Falls Convention were widely laughed at, the event inspired many anti-slavery activists to also work for women’s rights. And it was the first formal shot in the battle for the vote.

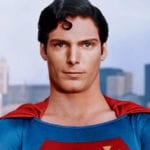

9A Change of Underwear

Amelia Bloomer was an activist working for the temperance movement when she attended the Seneca Falls Convention. Inspired, she soon started the first women’s newspaper, The Lily, which became a force for women’s rights. The Lily also asserted that changing your underwear could change your life. In Amelia’s time, women wore long skirts to hide their legs and ankles. Underneath those skirts were up to 6 kilograms (14 lb) of undergarments. These could include corsets, hoop skirts, and bustles along with voluminous cotton or flannel petticoats. The feminine ideal of the day was a delicate creature who found it hard to cope without the protection of a man—and since they were already coping with corsets that made it difficult to breathe, heavy petticoats, and a skirt that could easily trip them up, women did indeed seem to be fragile and in need of male help. Amelia, along with other advocates of women’s rights, happily ditched her weighty under-duds and took to sporting Turkish harem pants worn under a knee-length dress. When Amelia wrote about her new clothes, subscriptions to her newspaper increased by the thousands. Readers eagerly sought information about revolutionary piece of clothing that came to be known as “bloomers.” Since bloomers included pants (which made it obvious that women had legs) they were considered shocking. Unflattering cartoons, like the one pictured above, linked the new garments to smoking and other “unwomanly” behavior. The clothing caused such a fuss that most women gave them up. But bloomers also brought The Lily into thousands of households, introducing many women to the idea that they deserved the right to vote. That idea, unlike the fashion fad, didn’t fade away.

8The Afflicted

What did people do to pass the time without TV, smartphones, video games, or Listverse? The fact that Ben Franklin collected over 200 early American synonyms for being drunk (including afflicted, addled, buzzey, cherubiminical, fuddel’d, foxey, almost froze, fevourish, merry, and mellow) provides a clue. In 1790, the average American over the age of 15 annually consumed an estimated 34 gallons of beer and hard cider, five gallons of hard liquor, and one lonely gallon of wine. By 1830, folks had slowed down some, but they still drank three times what would be considered normal today. Unsurprisingly, American families were often devastated by alcoholism. If it was Dad who was always “halfway to Concord,” the law insisted that he still completely controlled the family decisions and all the finances. Predictably, there were often tragic results for mom and the kids. So women began to work against the sale of alcohol. Susan B. Anthony, who became the country’s most famous advocate for women’s suffrage, got her start as an anti-alcohol activist, as did many other early feminists. Religious ladies often joined the Women’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) to campaign against the sale of alcohol. In fact, by the late 19th century, the WCTU was the largest women’s organization in the country. This powerful group didn’t just work to close saloons—it took on everything from children’s rights to public health and prison reform. The religious, teetotal members of the WCTU were considered very moral, upright, and decent. So in 1881, when the WCTU took on the fight for women’s suffrage, it brought not only thousands of new workers but also a new respectability to the formerly radical cause.

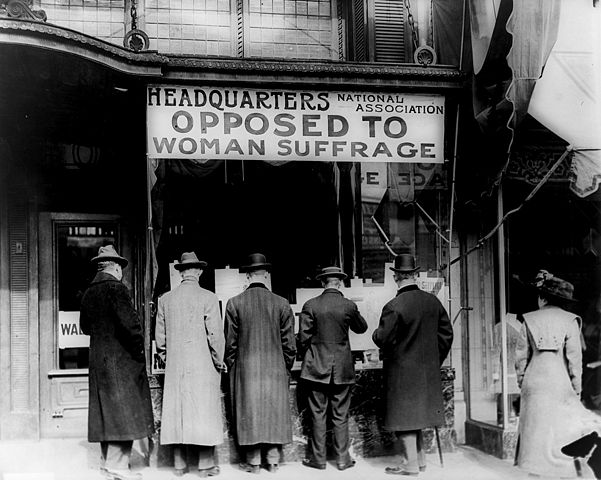

7Lonesome Cowboys

In 1869, Bill Bright, a Democratic legislator in Wyoming Territory, introduced a bill to give Wyoming women the right to vote. There were several political reasons why legislators found Bill’s bill a bright idea. Some racist legislators wanted white women to vote to overcome the “dangers” of the newly enfranchised male African-American vote. Some Democrats also hoped that giving women the vote would increase Democratic power at a time when Republicans held sway in Washington. But another key reason was that Wyoming had very few people. The Transcontinental Railroad was running through Cheyenne, cattle ranching was on the rise, and more settlers were needed—especially women. A bill for women’s suffrage would put Wyoming in the national news in a much more positive way than range wars did, and the publicity might bring in people. At that point, Wyoming had six men for every woman. If the territory offered women the vote, it might attract ladies to the state. In the East, anti-suffrage feeling still ran high. There were worries about everything from emotional women voters leading the nation into trouble to the fear that women would become so much like men that they’d turn into transvestites. In Wyoming, those lonesome cowboys wanted women around whether they voted or not. Wyoming’s all-male legislature became the first to give women the vote. The decision put heart into the suffrage movement and prominent leaders like Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton hopped on a train to visit “the land of freedom.” Taking in the lesson of Wyoming, suffragists lobbied hard in the West, and by 1896 there were four states where women had the vote: Wyoming, Colorado, Utah, and Idaho.

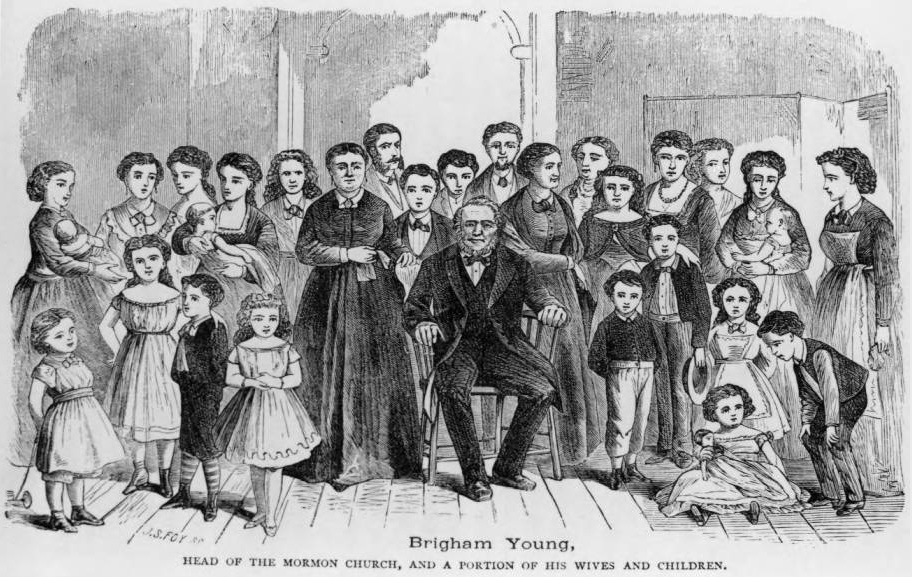

6Polygamy

One of the lesser-known forces that brought American women voting rights was the battle over Mormon polygamy in Utah. In 1847, Brigham Young, President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, brought his followers to what is now Salt Lake City. Young eventually became governor of the new Utah Territory, where he lived happily ever after, having married over 50 wives. When the railroad came to Utah and brought other religions to the territory, Young worried that his followers would be persecuted for plural marriage. Most non-Mormons considered the practice un-Christian, and they wanted it made illegal. Some opponents of Young thought that if women had the vote, they’d overthrow the power of their tyrannical husbands and polygamy would end. But the situation was more complicated than that. For example, one of the state’s most influential advocates for female suffrage was Emmeline Wells, the seventh wife of the Mayor of Salt Lake City, and the owner of the women’s newspaper, The Exponent. Wells wrote about the benefits of one husband being shared by several women (basically more time to work at your own thing while being supported by your sister wives) but she also wrote passionately about voting rights for women. Wells found a powerful ally in Governor Young, who eventually used his political influence to make sure that legislators gave women the vote. Young believed that supporting women’s suffrage would send a message that Mormon women weren’t enslaved and downtrodden. He also believed that Mormon women going to the polls would help keep him in power (and wives). That’s why, in 1870, the 17,000-plus women in the Utah Territory became the largest population of female voters in the world.

5Bicycles

In the 1890s, the introduction of affordable, mass-produced bicycles filled the streets with male cyclists. But when women decided to hop on their bikes, it became another “shocking” controversy. Much like the vote, the typical argument went something like this: Ladies will be corrupted by the freedom to travel on their own, lose all moral sense, try to act like men, try to take over, and the very foundations of society will be destroyed! The first women who tried to ride bicycles attracted stares and taunts. There were lectures from doctors that women would damage their organs and sermons from the pulpit that women on bikes were unchristian. But women still refused to give up their bikes. Instead, wealthy and influential ladies took up cycling in droves. They competed in cycling races and housewife Annie Londonderry Kopchovsky actually cycled around the world in the 1890s. Because cycling in long skirts was dangerous, bloomers made a huge comeback, skirts got shorter, and those pounds of petticoats were on the way out. By 1900, when the golden age of cycling was run over by the automobile, society’s picture of the “ideal woman” was finally changing to the “new woman” who was healthy and self-reliant rather than fragile and helpless. How did this apply to getting the vote? Women had learned that it was possible to overcome fierce opposition to gain their freedom. According to Susan B. Anthony, the bicycle had “done more to emancipate women than anything else in the world.”

4Electric Cars

One of the few things women didn’t have to fight for was the right to drive. Electric cars were easy to handle, clean, and quiet, and their manufacturers felt that those qualities made them perfect for female buyers. A 1909 Baker Electric tempted the respectable lady with a cozy interior of expensive fabrics and plenty of tassels. Ads encouraged women to drive electric cars on errands, shopping trips, and social outings. Since the world was still dedicated to the idea that women should stay at home, manufacturers also stressed that electric cars had limited mobility—so the little lady couldn’t stray too far. Electric car makers put women behind the wheel, and by the time conservative society began objecting, it was too late. Women were already driving gas cars to go farther and faster—and they didn’t just use their wheels for errands. Suffragists drove to rallies, which made it easier to schlep their luggage, signs, banners, and all those leaflets. Organizers could place a large banner on the back of their vehicle and campaign through the countryside, giving speeches from the car and collecting money for the cause. Cars also got women noticed. Two suffragists and a little kitten took a road trip “through 25 states in the good old USA,” attracting great publicity all along the way. Most importantly, driving helped women win elections. In 1911, when women were fighting to get the vote in California, suffragists embarked on auto tours, speaking and organizing in far-flung rural areas. Later that year, those same rural areas brought in the votes that narrowly enfranchised California women.

3It’s The Money, Honey

Though many women ridiculed the idea of voting when it was first proposed, financial considerations often forced them to change their minds. From the mid-19th century on, the industrial revolution offered new opportunities to women in the cities, where they earned far more than they could make back home on the farm. But although a working girl might get a taste of independence, once she was married all her wealth came under the control of her husband. If he gambled or drank away her profits, well, that was just too bad. When her husband died, a widow might find that her savings and home had been taken from her and given to her son and his family, even if she’d brought them into the marriage herself. Single women also found restrictions everywhere. Most labor unions, colleges, and high-status professions like medicine or law were for “men only.” Banks often didn’t allow a woman to open her own bank account. And since they couldn’t vote but still paid taxes, women endured taxation without representation. Many women soon sought the vote to change the laws that kept them poor.

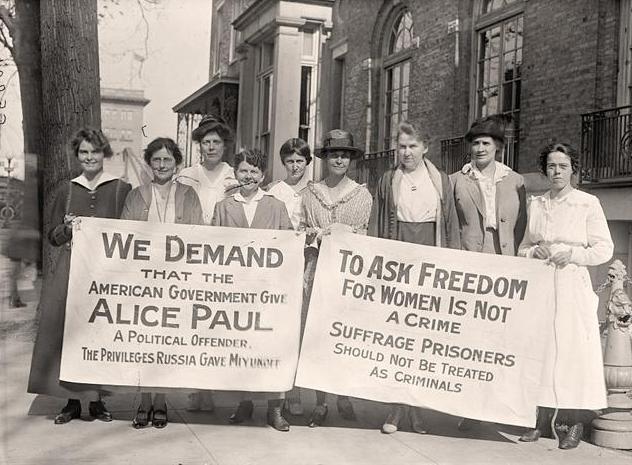

2A Jailhouse Deal

Pretty, fragile-looking Alice Paul was the head of the National Women’s Party (NWP) and America’s toughest general in the battle for the vote. Paul believed that President Woodrow Wilson had enough power over Congress to make them pass the necessary amendment, but he refused to get involved. In 1917, she confronted Wilson on his doorstep. NWP protestors (dubbed Silent Sentinels by the press) wordlessly picketed the White House day and night. While Wilson made foreign policy speeches calling for democracy and liberty around the world, the Sentinels held signs demanding “Mr. President How Long Must Women Wait For Liberty?” When crowds began to harass the Sentinels, instead of stopping the violence, the government had the protestors arrested for crimes like blocking the sidewalk. Patriotic judges handed down hefty jail sentences, and reports surfaced of respectable ladies enduring worm-infested food, isolation, and general mistreatment. Sympathy began to shift toward the NWP and, fairly or not, Wilson was often blamed for their imprisonment. That November there was a “Night of Terror” when Sentinels held in Virginia’s Occoquan Workhouse were beaten, dragged, and choked. Meanwhile, in a jail in Washington, Alice Paul was leading a hunger strike. Though very weak, she proclaimed that she would starve to death to get liberty for women. When NWP inmates appeared in court bruised and battered, the nation was outraged, and Wilson’s advisers urged him to “do something.” Paul was usually allowed no visitors, but a Washington journalist did visit her cell and might have offered a deal from the President. Within days of his visit, all the protestors were suddenly released and there were no Silent Sentinels picketing the White House over Christmas. Early in January, Wilson threw his support behind the 19th Amendment. The bill passed the following year. Wilson claimed that his support was a reward for women’s tireless war work, but there are suspicions that what he really wanted was no more grief from Alice Paul.

1Heroic Politicians

“Heroic” and “politician” don’t usually go together, but some of America’s male politicians were definitely suffrage heroes. In 1878, Senator Aaron Sargent of California—a friend of Susan B. Anthony and a steadfast supporter of women’s rights—introduced a bill nicknamed “the Susan B. Anthony Amendment.” It stated that no citizen could be prevented from voting because of their gender. Unfortunately, the bill took a while to pass. Forty years later, three congressmen went above and beyond to help the Anthony Amendment (now officially the 19th Amendment) pass the House of Representatives. Thetus W. Sims of Tennessee had a painful broken shoulder, but he not only showed up to vote with his arm in a sling, he also lobbied his Southern colleagues to vote for the bill, too. Indiana’s Henry Barnhart was carried into the House on a stretcher to give his vote. And Congressman Frederick Hicks of West Virginia obeyed his dying wife’s request to leave her bedside so he could make sure the amendment passed. But the drama wasn’t over even when the 19th Amendment finally won passage in both the House and the Senate—it still had to be ratified by at least 36 states. The press followed the frantic trip of West Virginia State Senator Jessie Bloch as he rushed home from a vacation in California because the governor had called a special ratification session. He knew the bill wouldn’t pass without him—and he arrived just in time to cast the vote that made West Virginia the 34th state to ratify the Amendment. Even more dramatic was the saga of 24-year-old State Representative Harry Burn. His vote made Tennessee the 36th state to ratify the 19th Amendment, and thus was the deciding vote in making women’s suffrage the law of the land. Desperate anti-suffragists demanded that Harry change his “aye” to “nay.” They accused him of taking bribes, ordered his mom to make him change his mind, and generally harassed him until he had to hire bodyguards. But Harry stood firm, proud of his action “to free 17 million women from political slavery.” Sue Steiner is a frazzled mom and the author of Uncle John Presents Mom’s Bathtub Reader. She’s also the author of the upcoming book Amazing Moms Who Changed The World. You can reach her here.