Things didn’t get any better when they made contact with the outside world. From the moment they first met the Europeans, the Inuit have gone through tragedy after tragedy. They have been taken from their homes. Their culture has been crushed, and countless lives have been ruined—all in ways that still affect them today.

10 First Contact With Europeans Ended In A Kidnapping

Martin Frobisher was one of the first European faces the Inuit saw. Frobisher met and talked with the Inuit—and then kidnapped three of them. Frobisher dragged a man, his wife, and their infant child into his boat and brought them back to England to show them off. There, they displayed their talents, demonstrating how they made kayaks and hunted animals. The European didn’t think highly of the Inuit. “They were savage people and fed only upon raw flesh,” one man wrote. His entry abruptly ends: “They died here within a month.” Unprepared for European diseases, the Inuit man fell ill and died nearly as soon as he arrived. His wife died the next week and their baby shortly after. The family was buried with only a short obituary left behind. “Burials in Anno 1577,” it read. “Collichang, a heathen man, buried the 8th of November. Egnock, a heathen woman, buried the 13th of November.”

9 They Were Put In Human Zoos

By the 1800s, Europeans had started gathering up all the exotic people they’d met in the New World and showing them off in human zoos. Some were kidnapped, and others were lured into it—but none of it went well. A man named Johan Adrian Jacobsen lured a group of eight Inuit, who started performing in European zoos on October 15, 1880. They didn’t last long. The first, a boy named Nuggasak, got sick and died within two months. The troupe went on, but 13 days later, Nuggasak’s mother died. “The husband is very sad,” Jacobsen wrote in his diary, “and expressed his wish to be able to accompany his wife.” Jacobsen denied his request. The show went on. Two days later, the man’s daughter died. The heartbroken father fought with Jacobsen to stay with his dying girl, but Jacobsen didn’t let him. They had to go to Paris. When they reached France, though, the last five Inuit were sick and had to be rushed to the hospital. By January 8, all five had died. “Everything went so well in beginning,” Jacobsen wrote as he watched the last of the Inuit die. He briefly mused over accepting the tiniest hint of responsibility: “Should I be indirectly responsible for their deaths?”

8 An Entire Tribe Was Wiped Out

At the turn of the 20th century, European whalers met a new tribe. They were called the Sadlermiut and lived on three islands in Hudson Bay. The Sadlermiut lived in complete isolation from the Inuit. They didn’t build igloos. Instead, they lived in stone houses. They had their own religion and their own language. They appeared to have been influenced by Inuit culture, but they were their own people with their own beliefs and their own lifestyle. Then, within a couple of years, the entire population was wiped out. European diseases spread among them quickly. By 1903, every single one of them had died.

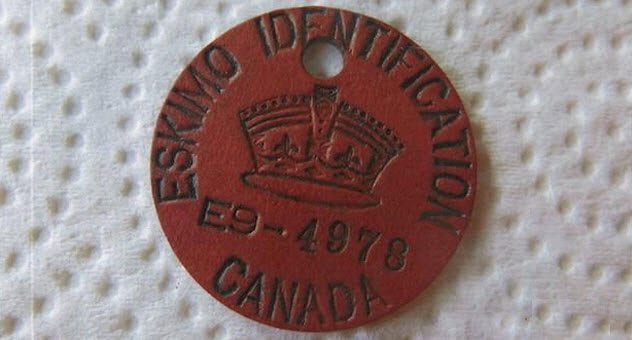

7 The Canadian Government Gave The Inuit Numbers For Names

The first missionaries to the North couldn’t pronounce the Inuit’s names, and they weren’t particularly interested in learning. Instead, the missionaries gave the Inuit new names taken from the Bible, like “Noah” and “Jonah.” The Inuit soon lost their family names, too. The Canadian government labeled each Inuit with an Eskimo Identification number that doubled as their last name. Their numbers were used as their last names on all government documents. The Inuit were also forced to wear their numbers around their necks like dog tags. By the 1940s, the Inuit went by names like Annie E7-121. They kept those names until disturbingly recently. The Inuit people weren’t officially allowed to use their own names (instead of numbers) until 1978.

6 People Were Forcibly Moved Farther North

In the 1950s, the Canadian government decided that it was time to tackle “The Eskimo Problem.” They told the Inuit that the government wanted to improve their lives by taking them to a new home with better game to hunt and fish to catch. It was supposed to be an easier life. Instead, the government relocated the Inuit to places like Grise Fiord and Resolute Bay, where the temperature on a winter night drops to -40 degrees Celsius (-40 °F) and the darkness of night lasts for five months straight. For the first year, people had to live there in tents without enough food or other supplies. Hunting was also much harder there. Most Inuit wanted to go home immediately, but they weren’t permitted to return to their homes for another 35 years. As it turned out, the government didn’t want to help the Inuit. The Canadian government just wanted the people living in the North to cement their claim to the Arctic against the USSR. The Inuit were moved north for “the strategic interests of Canada’s great neighbor to the south.” That’s not a conspiracy theory; that’s a quote from a government document.

5 The RCMP Slaughtered Sled Dogs

Before the 1950s, many of the Inuit still lived off the land. When the government tackled the “Eskimo Problem,” though, that changed. Every Inuit they could find was moved into new government-created settlements. The government promised the Inuit that this would lead to a new flood of wealth into their territory, but it didn’t really pan out that way. Instead, the Inuit lived in abject poverty in these settlements. It was worse now, though, because the Inuit couldn’t sustain themselves by hunting as they had before. Now they had to follow Canadian government laws that limited how much the Inuit could catch. These laws weren’t intended for people who lived off the land. Many Inuit kept hunting anyway—until the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) slaughtered their sled dogs. Claiming that these dogs were dangerous, the RCMP killed them by the thousands. Without sled dogs, it was impossible for the Inuit to hunt the way they had before. They were left to rely on their work as laborers. “I never understood why they were shot,” an Inuit man named Thomas Kublu later related. “I thought, was it because my hunting was getting in the way of my time as a laborer?”

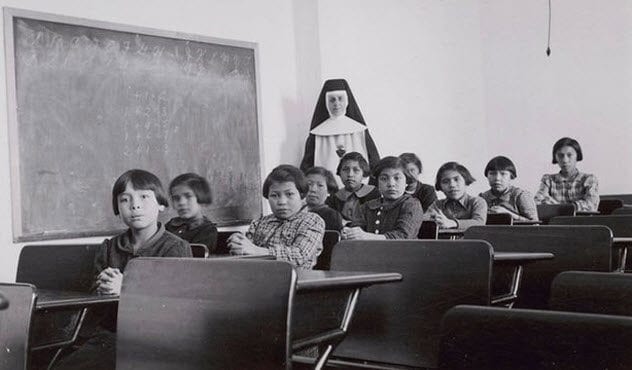

4 Children Were Separated From Their Parents

Once in the settlements, the children were sent to schools. Most of these towns, though, didn’t have schools of their own yet. So the kids were taken from their parents and sent to other provinces. Many parents believed that they would lose any financial support from the government if they didn’t send their kids off. These families were newly impoverished and unable to hunt as they had before, and so the parents let their kids go. In their new schools, the children were forced to speak English. Some have related that they were beaten if they spoke their own language, Inuktitut. They were taught a curriculum based on Southern values and languages. By the time they were sent back to their parents, they barely remembered their own culture. “I thought I was a Southerner,” one man related. “I didn’t want to come back. I didn’t like the tundra and the house.”

3 Children Were Abused

The children were sent to residential schools that were horrible. This is seen as one of the low marks in Canadian history, and it really was. At least 3,200 natives died in these schools, many from abuse and neglect. They were physically abused. If they spoke Inuktitut, one student recalled, they “had to put their hands on the desk and got 20 slaps.” If they didn’t stand during the nation anthem, they were beaten. Worse still, they were sexually abused. According to one student, a group of Catholic priests at one school made students “touch their penis for candy.” Another has said that she “was thrown into a cold shower every night, sometimes after being raped.” People reported the sexual abuse, but an active government campaign worked to block all investigations. Their staff was mostly volunteers, missionaries who were barely paid a dime. They were hard to replace—and so the government turned a blind eye to the abuse.

2 Substance Abuse

The Indian Act made it illegal for the Inuit to buy alcohol. In 1959, though, immediately after pulling the Inuit out of the lives they knew, the government decided to make an exception and let them drink. It wasn’t the best time to do it. The Inuit were going through an incredibly hard time and adjusting to a new sort of life. They didn’t quite know what to do with themselves in their homes and with their new lifestyles. They spent most of their time bored. So when liquor was introduced, they drank it. “Back then, the whole town would be drunk for a whole week,” one man recalled. “Everyone was hurting inside, not living as they should. People growing up with a lot of pain. I don’t want my grandchildren to grow up with that kind of pain and end up like us.”

1 The New Cost Of Living Is Unbelievably Expensive

Since then, things have improved. The Nunavut Land Claims Agreement has given the Inuit some autonomy, and the Canadian government has issued apologies for the past. Life in the North, however, is still far from ideal. The Inuit territory of Nunavut is the poorest in the country, and 60 percent of the people there can’t afford to feed their families. The average Inuit makes one-third the wage of the average Canadian, and the Inuit cost of living is significantly higher. Much of the Arctic is covered in permafrost, meaning that most food has to be imported from the South. That leads to some incredibly high prices. The people of Nunavut started taking pictures of the prices at their grocery stores, and they’re absurd. A cabbage can cost $28.54. A slice of watermelon goes for $13.09, 18 pieces of fried chicken fetch $61.99, and a 24-pack of bottled water goes for $104.99. Worse, though, is the lingering impact of everything that’s happened. Among the Inuit, the suicide rate for teenage boys is 40 times higher than it is in the rest of the country—a symptom of a culture that has been systematically destroyed. Read More: Wordpress