In recent times, archaeologists listened to music made millennia ago and saw miniatures of giant icons. They found bizarre objects in burials and personal items that belonged to extinct humans. Perhaps the most remarkable yield comes from small artifacts that reveal behavior, including mysterious cultural ways and even survival tactics used in the Cretaceous.

10 Unique Pencil

Scientists only became aware of Denisovans in 2008.[1] A small finger fragment revealed an entire branch of humanity that went extinct thousands of years ago. One group lived in Siberia, in a place known for great archaeological finds, including the groundbreaking finger bone. Called Denisova Cave, it yielded another unique item in 2018. It was a piece of hematite, a natural pigment that would have produced reddish-brown streaks. Indeed, the “pencil” (also described as a “crayon”) showed signs of use. Since the stump was found in a layer from 45,000 to 50,000 years ago, in an area of the cave where other Denisovan artifacts were found, the crayon could have belonged to them. However, at one point, the shelter was also home to Neanderthals, another extinct hominid and a good candidate for artistic tools. Although the newly discovered hematite is the only artifact of its kind to come from Denisova Cave, similar pencils were already known from another location, called Karabom Paleolithic site, located about 120 kilometers (75 mi) away.

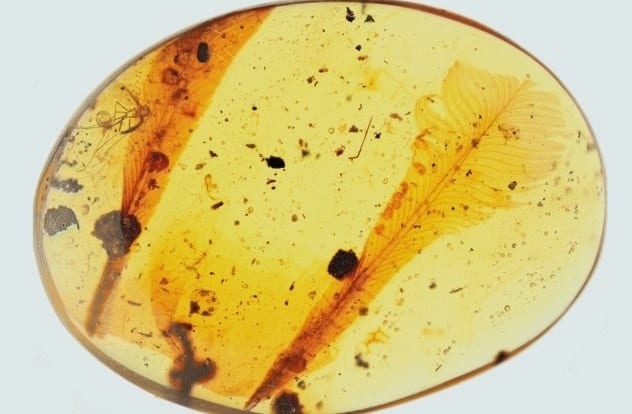

9 Decoy Feathers

In 2018, scientists examined 31 pieces of amber containing feathers from the Cretaceous.[2] Bird feathers from this era are not unknown. However, for decades, study was hampered, since all previous fossils were in a squashed state. These new amber samples provided a perfect look in 3-D, and paleontologists were astonished. Everything they knew about Cretaceous feathers was wrong. Previously, it was assumed that ancient birds had tail streamers for the same purpose as their modern cousins; to look good, especially during courtship. However, the ancient feathers were far from colorful. Additionally, they were built unlike anything today. The central shaft was not closed like modern birds’ but C-shaped, with an open underside. Incredibly, this shaft was thinner than a human blood cell yet rigidly supported side barbs. Several clues suggested that the feathers dislodged easily. The drab colors and ability for quick removal suggested that Cretaceous streamers were decoys. Their length ensured a greater chance that predators would grasp the tail and not the prey. In that case, the bird, somewhat plucked, could live another day.

8 The Pilatus Ring

During excavations in 1968 and 1969, a 2,000-year-old copper ring surfaced at Herodium.[3] Located southeast of Bethlehem, the palace once belonged to King Herod (74–4 BC). At first, archaeologists failed to notice the ring’s inscription. In 2018, special photographic techniques revealed an unexpected Greek engraving that read, “of Pilatus.” Pontius Pilatus, also known as Pontius Pilate, was the Roman prefect who condemned Jesus to the cross. Although Pilatus was a rare Roman name, and he likely visited Herodium while in Judea (AD 26–36), the ring probably was not his. It was a working ring, the type used as a seal, but a Roman prefect’s would have been one that displayed more bling, such as a silver or gold band decorated with gems. The simplistic copper ring also bore Jewish art—not a hot favorite of Roman prefects. One possibility is that one of Pilatus’s family members or workers used the name for their own seal. There is also the chance that a lower-ranked individual, with no connection to the prefect other than sharing the same rare name, owned the ring.

7 Unusual Indus Find

Together with Mesopotamia and ancient Egypt, the Indus Valley is considered one of the Old World’s cradles of civilizations.[4] It produced the mysterious Harappan culture, a Bronze Age people who lived the northwestern parts of South Asia. None of this was on the mind of Karl Martin when he rummaged through a yard sale in England one day. He just fell in love with a brown ceramic pot decorated with an antelope. After purchasing it for less than £4, Martin got practical. He assigned the small vessel the job of toothbrush holder, a duty it held for years. In 2018, he was moving vessels at the auction company where he worked when their decorations struck a chord. Remarkably, some of the paintings resembled the antelope on his bathroom jar. The technique used the same rough style to depict animals. When he took his pot to the auctioneers, experts determined it was made 4,000 years ago in Afghanistan. How this ancient artifact ended up in a car-boot sale in England is a mystery.

6 Mouth Harp

Around 1,700 years ago, somebody crafted tiny musical instruments from bone.[5] Owner and artifacts became separated, nearly two millennia passed, and 2018 arrived. It was during this year that archaeologists visited the Altai Mountains of Russia and discovered the five mouth harps. They were found at two sites called Cheremshanka and Chultukov Log 9. Locating the delicate, ancient instruments was delightful enough. However, researchers being researchers, they put the harps to their lips and tooted. Incredibly, one produced a sound, the same it probably played over 1,000 years ago. The noise was comparable to a flageolet, a flute-type instrument from the Renaissance. The working harp measured 10.9 centimeters (4.3 in) in length and 8.4 centimeters (3.3 in) wide. Just like the rest, the palm-sized instrument appeared to be made from ribs, harvested from horses or cows. The nomadic Altai craftsmen differed in this regard to other miniature harp makers across Central Asia, who preferred to use horn as their material of choice.

5 Bizarre Bird Skull Burial

In 2018, a project re-examined long-stored artifacts found in Tunel Wielki Cave in Poland.[6] When researchers opened one box, they discovered a child’s skeleton—minus the head. The youngster suffered from malnutrition and died, aged ten, during the late 18th or early 19th century. Beyond that, the story turned hazy. Oddly, the shallow grave was alone, not just in its own cave but all over the region, where not a single other cave burial existed. When researchers sought answers in an old photograph and the case notes, things got downright bizarre. The skeleton was discovered in the late 1960s, and right afterward, the skull vanished when it was sent off for analysis—but not before archaeologists recorded a strange burial practice. For unknown reasons, somebody placed the tiny skull of a bird (a chaffinch) in the child’s mouth. Pressed against the youngster’s cheek was another chaffinch head. The lonely grave was already mysterious, but the inclusion of two tiny bird skulls stumped the experts.

4 Woolly Mammoth Tiara

Denisova Cave in Siberia’s Altai Mountains is an archaeologist’s dream. The site has yielded exceptional finds, including the first remains of the elusive Denisovans, as mentioned above. In 2018, excavations in the same section turned up more bony pieces. This time, however, it was not a human skeleton but ivory. The tusk bits represent one of the rarest artifacts from Northern Eurasia’s Upper Paleolithic era—the tiara.[7] These personal items were made from mammoth tusk, antler, or animal bone. Nobody expected to find one at Denisova, and to boot, this could be the oldest one in history. The headband is an estimated 50,000 years old at the most. Researchers cannot say if the tiara belonged to a Denisovan, only that its curve fit a man’s head. The creation of the item required great dedication, including removing the tusks from the animal and softening them in water for shaping, followed by a finishing process of cutting, grinding, and drilling holes for strap ties. The purpose of Paleolithic tiaras is unknown. They could have been status symbols or, more blandly, bands to hold hair back.

3 Painting With Reptile Pee

Peru’s Paracas culture (900–100 BC) created colorful ceramics.[8] In 2018, 14 painted pots were analyzed, and the results delivered a mystery, a unique ingredient, and a slice of history. The pigments and ceramics were made at different times and places, but one thing stayed the same—the binder. This substance kept the paint intact. It was plant-based, but when scientists tried to identify the species, they failed miserably. The mysterious binder remains elusive, but a surprising ingredient came to light when the paint was examined. Two pottery pieces, bearing blue and white, had different pigments than the rest. They contained concentrated amounts of uric acid, which turned out to be reptile pee. Nobody knows how the urine was harvested or why it was mixed with the pigments. The pots also supported theories about how the Paracas dealt with neighbors. They were believed to have been influenced by a culture called the Chavin (900–200 BC). Paint on older vessels contained cinnabar, which was mined by the Chavin. Over time, the cinnabar’s use was replaced by red ocher. This suggested Chavin influence slowly deteriorated, as possibly did relations between the two cultures.

2 Rare Flax Wick

The ancient town of Shivta can be found in Israel’s Negev Desert.[9] It remains a mystery why this site was abandoned, especially since it thrived around the fifth to sixth centuries AD. In 2017, archaeologists re-examined items found in Shivta during the 1930s. The team happened upon a tiny treasure. A lamp wick doesn’t sound like much, but this was one of the rarest artifacts in the world. Back in the day, flax wicks were common, but since their sole purpose was to burn, few survived. In Israel, only two others had surfaced in the past. The 1,500-year-old strip, nestled inside a copper tube, measured a few inches long and was kept intact by the desert’s dry conditions. The linen was rough, which suggested that higher-quality flax was reserved for linen cloth and the subpar product for wicks. This did not affect the wicks’ ability to shine brightly; they glowed strongly without odor or smoke. This particular one was destined to illuminate a glass Byzantine lamp but, to archaeologists’ delight, was never used.

1 Miniature Terracotta Army

One of China’s most famous cultural icons is the Terracotta Army.[10] The first emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang, was interred in 210 BC inside an elaborate grave that included statues of life-size horses, chariots, soldiers, officials, and entertainers. In 2007, a pit was discovered near the city of Linzi. Inside was a super find, a sort of miniaturized version of the emperor’s ceramic army. The site yielded small musicians, infantry, cavalry, chariots, and watchtowers, all meticulously arranged. The 300 infantrymen stood around 22 to 31 centimeters (9–12 in) tall. The collection appeared to have been made a century after the Terracotta Army. Similarly, the figures were meant to grace the grave of a high official or royal. A good candidate was a prince called Liu Hong, from the city Linzi. Thus far, his tomb and body remain missing. However, elderly locals told researchers that once, there was a nearby hump. Aerial photographs from 1938 confirmed that a raised structure existed near the pit. It stood 4 meters (13 ft) high and resembled a burial mound. Sadly, it was razed by construction workers during the 1960s or 1970s. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages