Archaeology is sometimes seen as the “poster boy” of history by other historians. Its flashy discoveries often steal the limelight, grabbing the public’s attention like no textbook ever could. One archaeological find—like the discovery of Richard III’s body under a Leicester car park in 2014—can make a whole generation of academic writing obsolete in a second. And some of these finds are so strange that they can change the way we view history entirely.

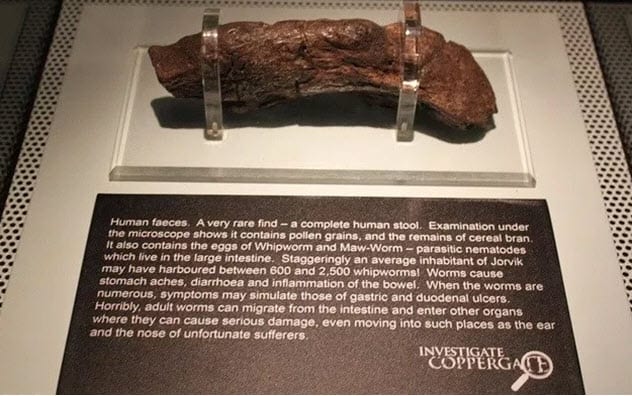

10 The Lloyds Bank Coprolite

The Lloyds Bank Coprolite, one of the strangest discoveries from the Viking Age, is unlike any other find from that time . . . because it’s a Viking defecation. It’s hard not to feel sorry for the poor man or woman who squeezed this out. At a whopping 19.5 centimeters (8 in) long, it is one of the largest human feces ever discovered. It was also densely packed—so much so that it fossilized instead of rotting like normal feces. Finds like this are extremely rare, but the moist earth of Jorvik kept it preserved. Now we can all stare at it and wince with sympathy for the poor person who created it—not least because it contained hundreds of eggs belonging to the whipworm, a parasitic worm which lives in the large intestine. Humor aside, this find is incredibly important because it gives us a fantastically detailed insight into the Viking diet, a subject for which it is nearly impossible to find concrete evidence. From this coprolite, we can see that whoever created it lived on a diet largely made up of pollen grains and cereal bran which they would have eaten in the form of bread and porridge.[1] The find is now on display in the Jorvik Viking Centre, a museum in York, UK.

9 The Leicestershire Bark Shield

In 2015, archaeologists working in Leicestershire, UK, made a discovery unique in the history of Europe—an Iron Age shield made from tree bark. The shield, which was created around 395–255 BC, turned the archaeological world upside down. Before this discovery, it had been widely assumed that bark shields wouldn’t have been strong enough to be used in actual combat. Although the shield was badly damaged when it was discarded in a pit used for watering livestock, it was over a decade old by this time and had seen plenty of action. Since its discovery, experimental archaeologists have attempted to recreate it. They have discovered that such shields could be surprisingly sturdy—even repelling arrows and weapon strikes—while being much lighter than a traditional wood or metal shield.[2] Otherwise, it was similar in shape and design to the metal shields discovered from the same period. The bark shield appears to have been painted with a red-and-white checkered pattern. Before this find, it was widely assumed that bark shields, if they existed, would have served primarily as sacrificial objects, being too weak to be used in warfare. Archaeologists now believe that they were probably widely used, particularly by poorer warriors. However, we don’t find many of them because the vast majority have rotted away and are now lost.

8 The Swedish Buddha

It is now widely known that the Vikings were prolific traders, maintaining trading posts from Ireland to Russia and going as far as markets in Baghdad and Egypt. However, nothing defines the Viking enterprising spirit better than a series of finds made on the island of Helgo in Sweden. Helgo was the site of a bustling Viking trading post for most of the early Medieval period, and in that time, objects from across the world ended up there. Among the finds were a statue of the Buddha, the top of an Irish bishop’s staff, and a ladle from North Africa. It is assumed that the ladle and bishop’s crozier were taken in raids because the Vikings often went pillaging in Ireland and Egypt, but the Buddha statue must have been bartered for. Made in Kashmir, India, around the sixth century, the statue was likely purchased somewhere along the trading route between the Middle East and Russia, where adventurous Vikings often traveled to trade, raid, or even join the Varangian Guard in Constantinople. The unusual statue was likely carried back to Helgo and sold to a local.[3] The find established as fact what some historians had suspected: The Viking trade routes stretched much farther than recently believed. While they probably didn’t travel all the way to markets in India, they often found themselves trading with Arabs, who would have in turn traded with India.

7 Ancient Egyptian Tobacco

One of the strangest archaeological discoveries of the last few decades happened in Munich, Germany, in 1992. Dr. Svetla Balabanova was performing a chemical test on some ancient Egyptian mummies which had been owned by the king of Bavaria. To her surprise, she discovered traces of nicotine and cocaine on them. In ancient times, both drugs could only be found in the Americas. Various hypotheses have appeared since then to try to explain how these traces came to be there. The most believable was that ancestors of the drugs existed in Eurasia at the time but went extinct before the modern day, much like the ancient Roman drug Silphium did. However, more recent studies have suggested that, theoretically, the ancient Egyptians may have had the maritime ability to make it to the Americas. Archaeological finds and ancient depictions from Hatshepsut’s voyage to the land of Punt have revealed a sophisticated naval infrastructure including harbors, construction materials, and the remains of the oldest seafaring vessels ever discovered.[4] Contemporary depictions of Egyptian ships show vessels over 21 meters (70 ft) long carrying over 200 sailors alongside goods which could only be found along the coast of Africa. This revealed ancient Egypt’s capacity for long-distance trade. There is one more tantalizing clue. In 1909, the Arizona Gazette reported that two explorers funded by the Smithsonian had discovered caves in America which contained Egyptian-style artifacts. However, no evidence exists today and the Smithsonian has no record of such a discovery ever being reported by any of their explorers. For now, this archaeological discovery remains a mystery.

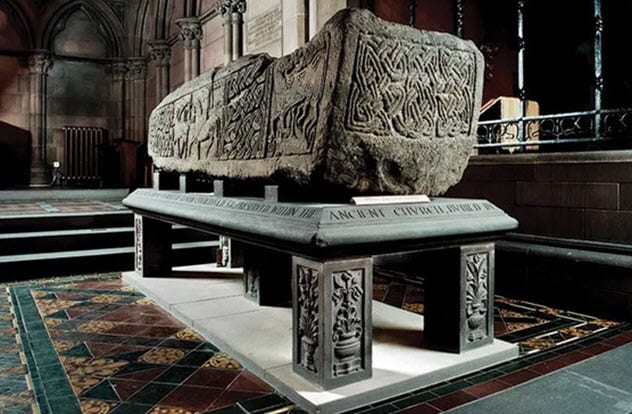

6 The Govan Stones

The Govan stones are examples of “hogbacks,” some of the strangest monuments to have survived from early Medieval Britain. Serving as sarcophagi for important figures like royalty or wealthy nobles, they only exist in places where both Norse and native British cultures are present. They have been found in Cumbria, central Scotland, and parts of Yorkshire. Featuring art and decoration that is a mix of Celtic and Norse styles, they seem to have been used to accentuate the importance of the dominant elite. They may have been used by newly arrived Norse dynasties to shore up their power and link their authority with the Celtic kings who came before them, an attempt to placate their newly conquered subjects. The Govan stones are a group of 31 sarcophagi that were built in Strathclyde around AD 870. They were built to honor the rulers of Strathclyde during a period when both Celtic and Norse leaders were vying for control of the kingdom. There were originally 46 stones. But when the stones were finally recognized as being of archaeological importance in the 19th century, only 31 of the stones were moved inside the Govan Old Parish Church. The rest were displayed against the church wall.[5] In 1973, the nearby Harland and Wolff shipyard was demolished along with a portion of the church’s estate. The 15 stones were considered lost, probably destroyed after being mistaken for debris. However, in 2019, three of the stones was rediscovered in the churchyard by a 14-year-old volunteer who was participating in his first archaeological dig. The Govan Heritage Trust is now expanding its dig in an attempt to find the rest of the lost stones.

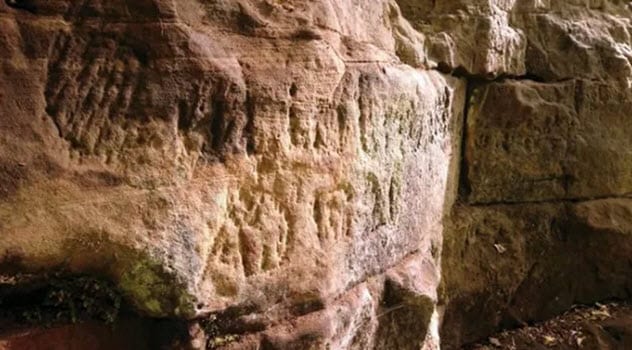

5 The Written Rock Of Gelt

In the early 200s, some Roman soldiers were working in a quarry in Cumbria, collecting rock for the construction of Hadrian’s Wall. While they were there, they decided to carve some messages into the stone. The engravings were officially rediscovered in the 1500s by William Camden, one of the first modern historians, and his friend Julius Cotton. After that, the site, which became known as the Written Rock of Gelt, was documented several times over the 1700s and 1800s. But the graffiti was never properly recorded. Since then, erosion has destroyed some of the messages, rendering some of them illegible. The site was easily accessible by the public until the path collapsed in the 1980s. Now the quarry is all but impossible to reach. Recently, the site was visited by archaeologists from Newcastle University, who had to descend 9 meters (30 ft) to reach it.[6] Fearing that they would lose the site to erosion entirely, the archaeologists made 3-D models of it so that future historians can study it. The models can be found at Sketchfab. Among other things, the soldiers wrote their names and those of their officers. In one instance, someone even carved a small caricature of one of their commanders. They also carved a penis. Of course.

4 The Orkney Temple

From the Pictish era onward, the Orkney Islands were sparsely populated and all but unimportant on a national scale. In the Iron Age that came before, however, Orkney was the site of one of the most advanced settlements in Britain. The purpose of this site is still disputed, and its many mysteries continue to stump archaeologists. By Iron Age standards, the central structure, Structure 10, was giant—25 meters (82 ft) long and 20 meters (65 ft) wide. The walls were huge—over five meters (16 ft) thick. They still stand over 1 meter (3.3 ft) tall today. Despite the building’s size, however, the inner chamber was only 6 meters (20 ft) wide. This is because there was another thick wall within, taking up much of the interior space. The main chamber was dominated by a large firepit in the center and decorated with large dresser-like pieces of furniture, the purpose of which is unknown. The roof was arguably the most impressive part of this structure. It was made up of stone tiles which had been shaped into perfect squares. The space between the inner and outer walls was carefully paved and may have been roofed, creating an interior corridor which looped around the inner chamber. The unusual building has led many to speculate that the site was some kind of temple, but its true purpose remains unknown. The presence of painted rocks, randomly scattered across the floors of two of the site’s buildings, only adds to the mystery. The most popular theory is that they had some kind of religious significance. One of the rocks was engraved with an image of the Sun.[7] Speculation over the site’s purpose ranges from a high-status private settlement for a chief to a kind of meeting place for different local tribes. One thing’s for certain: Despite being tucked away on an island in the far northeastern corner of the British Isles, this was one of the most impressive and advanced sites of Iron Age Britain.

3 The Tomb Of Philip The Arab

The story of a Roman-era tomb unearthed in 2018 gets weirder the more you read into it. The landscape of modern Bulgaria is dominated by burial mounds, some as tall as hills and visible for long distances. In recent times, these monuments have been plagued by treasure hunters who dig into them, take the inhumations left within, and sell them on the black market—a trade worth roughly $1 billion a year. As a result, legitimate archaeologists in Bulgaria have stepped up their efforts to excavate and protect old sites, removing finds of archaeological value and taking them to museums where they can be preserved. When a team started unearthing the Maltepe Mound, the biggest burial mound in Bulgaria, they found something arguably much more valuable: a gigantic Roman-era mausoleum. The team is now close to completing excavation of the entire south side. They now believe they’ve uncovered the tomb of a Roman emperor, Philip the Arab, and expect that it will become a site of global significance in time. They intend to excavate the whole structure, a process that will require government funding. Due to the structure’s age, it will almost certainly require reinforcing to stand on its own.[8] As they excavated it, no doubt some of the team members got excited over the prospect of finding treasure from the Roman era. Their hopes must have been crushed when they discovered the remains of a 40-meter-long (131 ft) treasure hunters’ tunnel which burrows straight under the southeastern corner of the tower. The team’s leaders said they expect to find things like cigarette butts and batteries inside such tunnels. In this tunnel, however, they discovered animal dung and coins from the reign of Sultan Suleiman the Magnificent. These treasure hunters dug this tunnel in the 1500s. Fortunately, the adventurers appear to have failed to loot the tomb. The archaeologists have found coins and pottery dating to the 200s, but it certainly was an unusual find.

2 Neanderthal Glue

For a long time, it was believed that Neanderthals just weren’t as intelligent or as advanced as Homo sapiens, but recent discoveries are turning that assumption on its head. In June 2019, archaeologists discovered evidence of Neanderthals using a primitive kind of glue on their tools. The find is between 55,000 and 40,000 years old, making these some of the oldest examples of adhesive being used to assemble human tools.[9] The adhesive seems to have been made predominantly from pine resin, but it also occasionally contained beeswax. The resin was cooked to a high heat over a fire as part of the process of making an organic glue which was used to coat a notch in a shaft of wood. A flint blade was then slotted into the notch and held in place. It is not the first of its kind of find, and it helps solidify the belief that the practice was widespread among these early humans. It also means that there is now more evidence that Neanderthals could create fires as and when they needed them—another issue that has been the subject of much debate over the years.

1 Extremely Old Houses

In architectural archaeology, there is a concept called the “vernacular threshold,” which is the oldest age that the dwellings of average people can be and still exist today. While buildings like castles and monuments have existed for thousands of years, the homes of common people are usually made of more perishable materials and rarely survive into the modern day. For years, the vernacular threshold in England was considered to lie somewhere in the late 1600s. It was believed that homes built before 1660 could not, for the most part, have survived into the modern day because they would have suffered too much wear and tear. A comprehensive study has blown that assumption apart.[10] The project focused on surveying 86 of the 3,000-odd peasant cruck houses which dominate western England and Wales. They found that nearly all of them were built during a period known as the “Great Rebuilding,” the years from the 1260s to the 1550s, making them at least more than 100 years older than previously thought. Contrary to what was previously believed, even the homes of normal rural peasants were built to last. Some of the homes had been built with the wood of more than 100 trees, suggesting a near-industrial level of tree farming even as early as the 1300s when the plague ravaged Europe. Many of these homes are located in the Midlands, an area famous for containing several ancient forests including Cannock Chase and Sherwood Forest.