The myth is further found in Scandinavia, Wales, France, Germany, and the Slavic nations of Central and Eastern Europe. Despite this, the tradition of the Wild Hunt has not been deeply documented. This has allowed for rampant speculation.

10The Mythical Leader Of The Hunt Changed

In Scandinavia, the hunt’s appearance was presaged by the loud barking of Odin’s hounds. When this occurred, it was widely believed that war was on the horizon. Meanwhile, in Germany, the pagan god of the wind and death frequently takes Odin’s place at the hunt’s lead. Outside of Germanic Europe, other figures were said to lead the huntsmen. In Brittany and Wales, King Arthur was frequently depicted as the leader of the hunt, while in central France, a mythical character named the Great Huntsman of Fotainebleau was said to have warned French citizens of the murder of King Henry IV and the French Revolution.

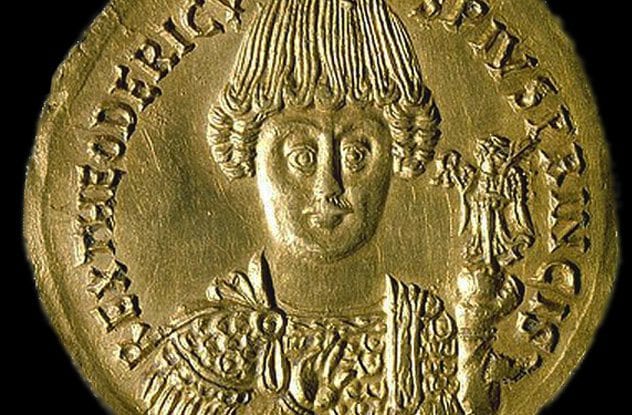

9Historical Leaders Were Part Of The Wild Hunt, Too

In one story from the German Rhineland from around 1250, Theodoric the Great, the Ostrogoth king who ruled over a conquered Italy in the fifth and sixth centuries, encounters the Wild Hunt as he tries to rescue the maiden Babehilt from the huntsman Fasolt, a giant who rules the forest with a vicious pack of dogs. For the medieval Germans, Theodoric the Great’s conquest of the evil Fasolt was a way to remind them of their own heroic heritage. For later people, the Wild Hunt took on a much more menacing aspect. In these cases, the devil was frequently seen as the hunt’s leader. If not the devil, then rakish rogues like Sir Francis Drake were substituted.

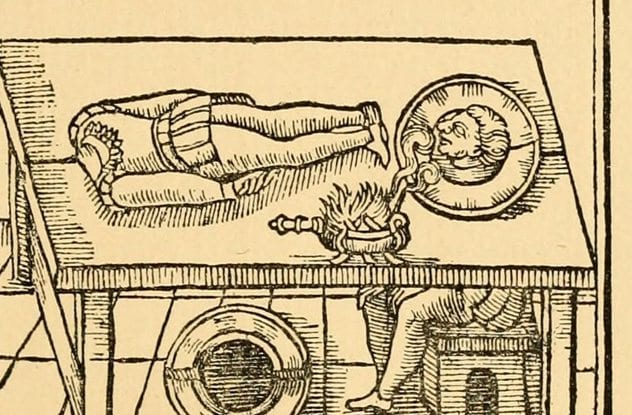

8The Hell Wain

In medieval England, the Hell Wain was a type of death coach that behaved similarly to the Wild Hunt. According to 16th-century author Reginald Scot, the English author of The Discoverie of Witchcraft, one of Europe’s first openly skeptical works on black magic, the Hell Wain was supposedly a wagon that came up from hell and could be seen on certain nights in the sky. On Earth, the Hell Wain would collect all the souls of the damned and drag them down to their everlasting torment. In Ireland, the Coiste-Bodhar performed a similar function. In the 19th century, West Virginians told tales about a ghostly black hearse drawn by a pair of headless white horses, while in the 20th century, the hearse was updated to a black automobile.

7The Witches’ Sabbath

Ronald Hutton, a professor of history at England’s University of Bristol, has a unique view of the Wild Hunt. For starters, he believes that the most common depiction is a synthesis of several different myths created by Jacob Grimm. On top of this, Hutton believes the ancient story of the Wild Hunt directly influenced ideas about the Witches’ Sabbath in Early Modern Europe. Specifically, Hutton argues that the roots of the Wild Hunt stretch deep into the history of northern Europe. For instance, he references Tacitus’s claim that the Harii tribe would paint themselves black and attack their enemies during the night. This was intended to invoke either the Einherjar, the ghostly soldiers of Odin, or simply angry specters. Later medieval records from northern Europe speak of ghostly or demonic hosts in the night sky. These stories, which had been in circulation in European villages for centuries, formed the basis of the Witches’ Sabbath, which usually involved children being abducted by flying witches.

6The Benandanti

The myth of the Benandanti werewolves is particularly strange. They transformed on four different nights of the year to journey to hell to battle evil witches known as the Malandanti. According to historian Carlo Ginzburg, their mythology shared certain overtones with the Wild Hunt. For instance, the Benandanti believed that while they slept, their spirits traveled through the night to protect their neighbors from harm. Also, like the Benandanti (many of whom were tried for Satanism and witchcraft in the Italian region of Friuli in the 16th and 17th centuries), those who claimed to have witnessed the Wild Hunt were frequently tried for supernatural crimes.

5A Larger Mystery Cult?

In writing about the Benandanti, Ginzburg saw them as part of a pre-Christian tradition widespread in rural Europe. In particular, Ginzburg articulates that prior to the Inquisition and the Catholic Counter-Reformation, northwestern Italy was home to an indigenous folk magic tradition intricately tied to the natural world. In a similar vein, Austrian scholar Otto Hofler believed the Wild Hunt pointed toward a continuity between Germanic paganism and German folk customs under Christianity. While Hofler’s ideas have lost much of their appeal thanks to Hofler’s close association with Heinrich Himmler’s Ahnenerbe project, there is something compelling about his notion that the Wild Hunt, formed a kind of ancestor worship that echoed the mystery cults of the Mediterranean. Specifically, Hofler argues that the participants in the Wild Hunt celebrations formed a type of secret society that was the Germanic equivalent of the Mithras mysteries.

4The Specter Of Herne The Hunter

A slightly menacing figure in English folklore, Herne the Hunter is said to be the lord and ruler of Windsor Forest and Great Park, both in Berkshire. Shakespeare even mentions him in The Merry Wives of Windsor, having Mistress Page speak of how Herne the Hunter sounds his horn, turns milk into blood, and shakes a chain at midnight during the winter months. Some Anglo-Saxon versions of the Wild Hunt legend claim that Herne the Hunter would lead the hunt on certain nights. Margaret Murray asserted that Herne the Hunter was a version of the ancient Celtic god of witches. He was part of a broad, pre-Christian underground religion that included such things as fertility rites and the Wild Hunt.

3Corpse Paint?

Although first worn by the likes of Kiss, Alice Cooper, and Arthur Brown, corpse paint—the blending of white and black greasepaint to create a garish, horrifying visage—has many different stories attached to it. Some claim that it has its origins in the Black Death and certain macabre performances that would heavily make up those actors performing the role of the plague dead. However, Austrian black metal musician Kadmon articulates the notion that corpse paint has its origins in the Oskorei, or Wild Hunt traditions of both Scandinavia and the German-speaking regions of the Alps. In particular, Kadmon states that Oskorei participants were young men who rode through the night during the winter and punished those who did not follow local customs. Kadmon, whose arguments aren’t widely supported, also shows how modern Perchten parades in and around the Alps contain echoes of the Wild Hunt.

2The Furious Host

Another common name for the Wild Hunt in medieval Germany was the Furious Host. According to tradition, the fury came from both the wind and the thunderous riding of Wotan (or Wodan) and the souls of dead. A euphemism for death used to be “joining the old host,” underlying that the Furious Host was as much of a death ritual as anything else. Once again, Kadmon links the Furious Host with black metal (which also comes from northern Europe, after all). Like other rituals associated with death, violence, and rebirth, Kadmon has argued that one part of the Oskorei ritual included making frightening noises. For the most part, the nocturnal actions of the Oskorei participants would not be out-of-place in a modern Halloween celebration.

1The Wild Hunt And Yule

Long before the coming of the Christian Yuletide, which celebrates the birth of Jesus Christ, ancient Germanic pagans celebrated Yule. Activities associated with Yule included gift-giving, sacrifices to the gods, and feasting. The 12 days of Yule, which roughly corresponded with December 25 through January 6, were considered a time of great magic and a time when the fates turned in a different direction. More importantly, Odin rode freely during Yule because the demarcation lines between the living realm and the land of the dead were thin and permeable. As such, Odin and his horsemen would ride through the sky in search of weary souls. It’s interesting to note that the Wild Hunt’s closest parallels in the modern world, such as Krampus and the Perchta/Berchta celebrations of Switzerland, Austria, Slovenia, and elsewhere, all take place around Christmas. Benjamin Welton is a freelance writer based in Boston. His work has appeared in The Weekly Standard, The Atlantic, Listverse, Metal Injection, and other publications. He currently blogs at literarytrebuchet.blogspot.com. Read More: Twitter Facebook The Trebuchet