Throughout history, mankind has engaged in one war after another. It seems like nothing could be left to amaze us. And yet, the following discoveries reveal secret, surprising realities that shaped one of humanity’s most ancient pastimes—warfare.

10 Roman Soldiers Were Cremated In Cooking Pots

Roman soldiers weren’t always privileged with a dignified send-off as archaeologists were reminded at a 1,900-year-old Roman camp near Tel Megiddo, Israel. The Legio camp is the grandest imperial base found so deep into the eastern portions of the empire and housed the Legio VI Ferrata, or Roman “Ironclad” Sixth Legion, who quelled uprisings and maintained Roman interests in Syria Palaestina. At the camp, researchers came across cooking pots that held cremated soldiers. It’s a gruesome and horrifyingly common discovery according to archaeologists who stumbled upon similar cremations around the Mediterranean.[1]

9 Veterans Lived With Terrifying Injuries

The warriors who died in battle may have been the fortunate ones when compared to those who survived with life-altering injuries, like an elite Scythian Iron Age warrior unearthed at the Koitas burial site in Kazakhstan. When he died more than 2,500 years ago, the apparently well-fed man was between the ages of 25 and 45 and unusually tall at 170 centimeters (5’7″)—which was 8 centimeters (3 in) taller than average.[2] He spent a portion of his years in agony because he had been shot in the spine with a bronze-tipped arrow. Luckily (or unluckily), it had missed all the delicate local blood vessels and spared his life. The vertebra healed around the tip, fusing the 5.6-centimeter (2.2 in) arrowhead to his spine.

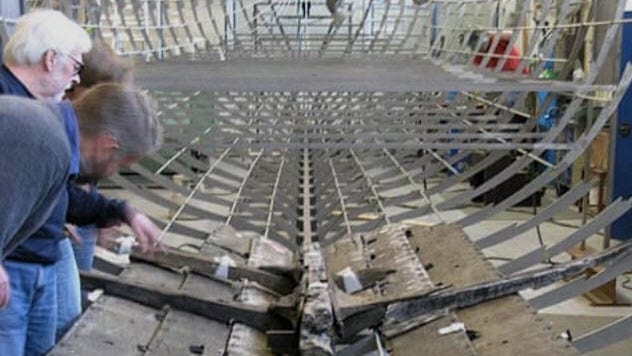

8 Vikings Built Speed-Demon Warships

The Danish king Cnut the Great ruled Denmark, Norway, and England with a fleet of advanced warships. And few were greater than the Roskilde 6, recovered from Denmark’s Roskilde Fjord. Roskilde 6 was a troop carrier built around 1025. The culmination of 30,000 hours of work, it held 100 Viking soldiers. Between sips of ale or mead, they would take turns working the huge ship’s 39 pairs of oars. Roskilde 6 is sleek with low sides so that warriors could quickly disembark and preemptively pillage Europe’s northern coasts. According to a re-creation built and sailed in 2007, it could maintain an average speed of 5.5 knots with a 20-knot top speed.[3]

7 The Romans And Germanic Tribes Sometimes Got Along

A bronze Roman horse head discovered at a Roman settlement near Frankfurt suggests that Roman-Germanic relationships didn’t always devolve into bloodbaths. Romans generally took Germanic peoples’ land by force. But a gilded bronze horse head and equally benign artifacts found at the Roman settlement Waldgirmes show a more friendly relationship. Oddly, the settlement sprawled across 20 acres but there were no military buildings. Instead, it had woodworking shops and civilian structures, like an administrative center decorated with four bronze, gold-covered horsemen—the origin of the 2,000-year-old horse head in question. For a short time at least, the Romans and their enemies lived in peace and traded—until a crushing defeat in AD 9 forced the Romans to flee.[4]

6 A Viking’s Best Defense Was Offense

Scientists rediscovered Viking battle tactics, which involved a lot of offensive shield thrusting, by dressing up in protective gear and shield-thrusting each other. The replica round shield, 1 meter (3 ft) across and made of pine planks covered with pig leather and raw ox hide, was based on shields unearthed in northern, Viking-infested areas. It didn’t fare well when passively absorbing blows. But the shield was much more effective when used actively to unbalance and charge opponents. As silly as the experiment may sound, the simulated damage matches the wear and tear on ancient shields, supporting the researchers’ findings.[5]

5 Soldiers Used Pottery Shard ‘Post-its’

Pottery shards (ostraca) were the Post-it notes of the ancient world. They were used to record military orders or, in the case of a 2,500-year-old message finally revealed via new imaging techniques, to send messages between soldiers stationed at distant outposts. The message was inscribed on a pottery shard (a more practical alternative to papyrus) from Israel at what used to be the fortress of Arad. It immortalizes Hananyahu, a soldier who lived around 600 BC and whose invisible ink–inscribed message remained hidden since its discovery in 1965. What does the super secretive note contain? Enemy positions? Attack strategies? Nope, a plea to his friend Elyashiv to send more wine.[6]

4 ‘Indian’ Charioteers Were Among The Ancient World’s Finest

At Sinauli village, archaeologists found three 4,000-year-old Bronze Age chariots in burial chambers. They belonged to a mysterious but mighty “warrior class” as suggested by other discoveries, including a helmet, daggers, and copper-hilted sword. The burial chambers and graves themselves were loaded with more copper, including sophisticated luxury items like beads, a mirror, and “anthropomorphic figures.” All of them required master craftsmanship and suggested royal burials. According to researchers, with their copper-studded armament and chariots, these unidentified warriors could have held their own against their more famous counterparts from Greece or Mesopotamia.[7]

3 Barbarians Practiced Gruesome Death Rituals

The oldest evidence of mass warfare in northern Europe dates back to around 2,000 years ago. The remains of a barbarian-on-barbarian battle left behind a pile of bodies dumped into a bog, highlighting a creepy postwar ritual. More than 2,300 bones were found. They belonged to about 80 people who fought and died sometime between 2 BC and AD 54. (However, many more were involved in the battle.) Combatants ranged from 13 to 60 years old, but the real surprise was the treatment of the bones. Some pelvises were threaded on a tree branch, and the rest were gnawed on by animals, probably because they’d been left out six months to a year before being dumped. Mysterious cuts on the bones may suggest that the victors marked the dead before chucking them in the bog.[8]

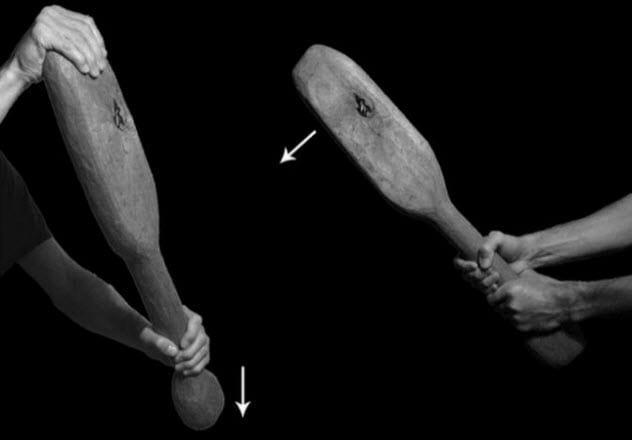

2 Neolithic Warriors Used Deadly Wooden Clubs

Neolithic warfare conjures images of men swinging wooden clubs. But those wooden clubs were surprisingly effective, says modern science. Archaeologists recently recovered one such 5,000-year-old, waterlogged, wooden club from the Thames. They found it extra lethal due to its longer-range “blade” and a weighty pommel used for close-range smashing. After dating it to between 3530 and 3340 BC and naming it the “Thames Beater,” they tested it out on a synthetic human head built for military ballistic testing.[9] Yes, it could break your skull, which may not be surprising. But researchers matched the type of wound with that found on a fractured Neolithic skull, illuminating a brutal ancient murder scenario.

1 Warrior Women Received Grand Burials

The man’s burial space had been looted, but the woman’s had not. In addition to war items like over 100 iron arrowheads and a horse harness, she was buried with a bronze mirror, two golden bracelets, golden pendant earrings, a golden vial full of incense, and an ancient Hebrew-inscribed gem that bears the name of “Elyashib,” a Judean commander. It’s an exceedingly rare collection. The items probably changed hands numerous times as generational hand-me-downs before finally being interred.