10 Unguentarium

Like the ancient Egyptians, the Romans took their funerary practices seriously lest the dead remain eternally trapped in uneventful purgatory. A by-the-book funeral could consist of five parts, starting with a procession and ending with a grand feast to ensure the departed’s successful voyage to the immortal domain. Afterward, Romans celebrated the dead during specified “holidays,” kind of like Mexico’s famed Day of the Dead. Strangely enough, gravesites throughout the Roman world often surrendered vaselike sculptures called unguentaria. According to legend, they held the tears of family members grieving over the departed, although that appears to be a romantic myth. It’s now generally agreed that unguentaria—“unguent” meaning “ointment”—stored perishable goods for the living rather than commemorations for the dead. Unguentaria served as old-timey equivalents of plastics, and the specimens unearthed contained cosmetics or fragrances. In his terrestrial treatise, Natural History, Pliny the Elder records that Romans preferred scents of marjoram, roses, and saffron. He also said that the women of the house utilized as many beauty products as women do today, including lotions for soft, smooth skin.

9 Fetus Paper

Before the days of Office Depot, paper was a luxury that was often made from less than savory ingredients. For example, the first collection of portable Bibles in Europe, all 20,000 of them, was said to be printed on parchment made from stillborn barnyard critters. Known as uterine vellum, or abortivum parchment in Latin, these names suggested that the supremely thin pages came from calf and sheep fetuses. To put the issue to rest, an unexpectedly large collaboration between British, Irish, French, Danish, Belgian, and American scientists devised an innovative way to test the delicate paper without destroying it. They used a rubber eraser. After a good rubdown, the electrostatic charge elicited from the eraser-on-paper action attracted tiny protein fragments from the pages. Analyzing the meaty dust revealed that the vellum was not, in fact, gruesomely manufactured from aborted animals. Instead, it was made from cows or other hoofed adult animals as per tradition. How medieval artisans were able to create such fine, thin sheets remains a mystery for another day.

8 Unexpected Mummy

Peru’s 5,000-year-old Caral-Supe (aka Caral) predates the Mayan, Incan, and Aztecan cultures by thousands of years. The 630-hectare, pyramid-boasting sacred site is South America’s oldest center of civilization and marks the start of city living in the region. Due to a lack of records, we know little of ancient Peruvians, but a recently discovered female mummy suggests a progressive culture that valued women and men as equals. The 4,500-year-old corpse reposed in the ruins of Aspero, a quaint fishing village 25 kilometers (15 mi) from Caral and under the auspices of its mysterious creators. The circumstances of the woman’s burial indicate her importance. Likely between the ages of 40 and 50 when she died, archaeologists found her laid to rest in the fetal position and placed atop a variety of charms. These included four figurines (known as tupus) carved in the likenesses of monkeys and birds, a seashell necklace, and a pendant made from a Spondylus mollusk. The circumstances of the woman’s burial and the recovered items offer evidence that women could attain high status just as men could—a historical rarity and a candid glimpse into the hidden life of the Norte Chico peoples.

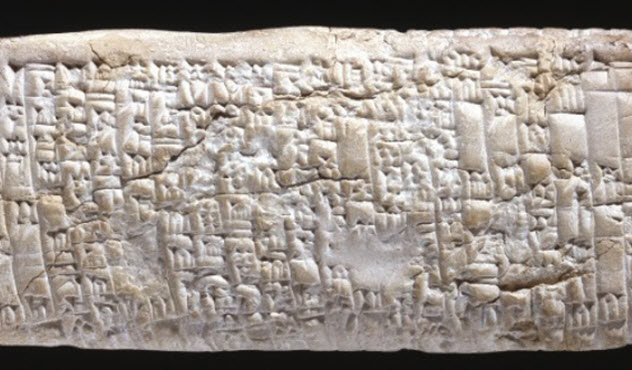

7 Etruscan Slab

The supremely religious Etruscan culture imparted great knowledge to Greece and Rome and left behind an ugly alphabet. Sadly, we don’t know much of their language, and most of what we’ve gleaned comes from funerary stones or inscriptions on household knickknacks. Recently, archaeologists have unearthed a cipher of sorts on an old slab unearthed from beneath an Etruscan temple that dates back at least 2,500 years. It’s one of the longest, most substantial pieces of Etruscan literature ever recovered, containing at least 70 legible characters that are all nicely punctuated and a bevy of new words and phrases. The chipped, burned slab survived remarkably well, considering it was used as part of the foundation and bore the temple’s weight on its stony shoulders. Similar tablets have provided windows into the surprises of everyday Etruscan life, like a female version of the Greek Olympics that included topless javelin and bare-breasted equine events. In fact, women enjoyed many freedoms withheld from their Grecian and Roman counterparts. Etruscan women were allowed to enjoy wine, socialize freely, and train as soldiers.

6 Jockey’s Monument

The Anatolian province of Konya served as the capital to the Seljuk culture of 1,000 years ago and afterward flourished as a prominent Ottoman city. It housed a hippodrome and horse-breeding center of some import according to a 2,000-year-old tablet, which paints Konya’s bygone inhabitants as avid race fans. In the Beysehir district exists a monument to a once-famous jockey and bachelor named Lukuyanus, who died at a young age before fulfilling his jockeying potential. So a memorial was carved into the sacred Anatolian mountains to honor the youth after his tragic death. On it, archaeologists found still-legible text, including a lament to the unmarried hero and some information on the gentlemanly pursuit of horse racing. The stone-etched document describes one long-abolished cardinal rule that would demolish modern horse racing as a profitable business: Winning horses were disqualified from further races. Victorious owners were excluded along with their horses in a magnanimous effort to share the wealth.

5 Chinese Gnomon

The ancient Chinese looked to celestial bodies to forecast the future affairs of men and developed an array of fancy stargazing tools to do so. These included gnomons, simplified sundials of Babylonian invention that were used to measure the Sun’s declination. The earliest Chinese gnomons were sticks, which were set out at midday along the north-south axis. The length of the shadow cast indicated solar slant and the changing seasons, useful agricultural information that also led to the construction of calendars. A more sophisticated, two-piece version was found in the over 2,000-year-old tomb of a Western Han dynasty marquis known as Xiahou Zao. For a while, it was known only as “lacquerware of unknown names.” Finally, it was realized that the two pieces belonged together to form a latitude-specific equatorial display. The gnarliest gnomon was developed over 600 years ago by Guo Shoujing during the Yuan dynasty. It used a taller crossbar and longer base to accurately measure the length of the shadow and therefore the Sun’s height in the sky.

4 Roman Wine Vessel

The ancient Romans’ sense of humor did not adhere to modern principles of modesty but would have fit right in on the Internet. Case in point, an 1,800-year-old Roman drinking vessel covered with phalli. The phallus cup was unearthed over 50 years ago, probably in Great Chesterford, Essex. But it was denied to us for the half a century that it collected dust in the private collection of Lord Braybrooke. The vessel comes from a Roman camp where Rabelaisian soldiers—on break from pillaging Britain’s precious metals—quaffed diluted wine from it and laughed at its raunchy depictions like common frat boys. One scene looks like it came straight from a reddit joke: A nude woman commands a chariot pulled by four disembodied phalli. Observant naturalists, the Romans realized that the male organ has no natural means of locomotion, so in their representation, they have innovatively grafted chicken legs onto each phallus.

3 Quids

The Anasazi (aka Ancestral Puebloans), the predecessors of the Pueblo culture of today, populated the American Southwest as far back as AD 100. Research shows that they enjoyed a common vice—chewing tobacco. From the prehistoric equivalent of a compost heap found in Antelope Cave in Arizona, archaeologists recovered 345 small, fiber-wrapped balls of unknown purpose. Dubbed “quids,” similar bundles have popped up across the American Southwest, often embedded with teeth marks. At first, it was assumed that old-timey folk chewed on these during periods of food scarcity to simulate eating and to draw in the tiny bits of trace nutrients that remained. Then researchers checked the bundles under a microscope. Peering deep past the 1,200-year-old fibrous coating, they discovered that the quids contained several types of wild tobacco, including coyote tobacco (pictured above). It’s likely that the tobacco fed daily addictions rather than sacred yearnings because the used quids were found in the trash. But many others have not been tested, and researchers are excited about what other substances may be inside.

2 Lake Baikal ‘Venus’ Figurines

The ideal female form is a popular motif for ancient sculptures, including the Mal’ta figurines recovered at Angara River in Russia’s Siberian Irkutsk Oblast. Or so it seemed. But magnification unveiled the figures as faithful depictions of the Mal’ta-Buret’ women, men, and children that lived 20,000 years ago. Carved from mammoth tusk, most were supposedly female nudes. So archaeologists borrowed a set from Russia’s Hermitage Museum for, uh, research and threw them under a microscope. The scans revealed a glut of detailed garments—they aren’t nude at all, only smoothed over by time and dirt. The figurines are clad in period-specific clothing such as bracelets, hats, shoes, packs, and bags. With other features invisible to the naked eye, artisans labored to create different hairstyles and even used different cuts to give the illusion of fur or leather. Overalls seem to be overwhelmingly popular, as are a variety of furry helmets and hoods to keep the cold out. Mysteriously, the figurines are scored with tiny holes, presumably so they can be worn as charms or ornaments.

1 Babylonian Complaint

Shysters have always existed, and some have even been immortalized. For example, Ea-nasir appears on a nearly immaculate Babylonian complaint tablet recovered from Ur, one of Mesopotamia’s ancient capitals. An ancient 0-star review, the nearly 3,800-year-old grievance was filed by a disgruntled customer, Nanni, against Ea-nasir, a shady businessman and purveyor of copper. The unscrupulous merchant promised Nanni a quantity of premium copper yet delivered ingots of downright insulting quality. So Nanni sent messengers multiple times to exact a refund and apology from Ea-nasir. But Ea-nasir only offered salty remarks, and the messengers were sent back through enemy territory without money each time. The tablet only recently gained fame. But it was translated way back in 1967 by Assyriologist Leo Oppenheim, who published the story and others like it in his book Letters from Mesopotamia. The tablet itself resided in what is believed to be Ea-nasir’s house. Though given everything we know about his unsavory character from this letter, he probably kept it for laughs.