But perhaps the most revealing stories come from the teenagers who never lived to grow old. How they lived and what caused their untimely deaths can paint vivid images of their struggles, games, places in the community, and the social problems of the time.

10 Girl From Cerro Juanaquena

While scouting for a location to build a new solar plant, archaeologists unearthed an ancient camp. Situated near the Santa Maria River in Mexico, the 10,500-year-old site was a toolmaking center used over many generations. Excavations in 2014 revealed over 18,000 related artifacts, including stone flakes and cores, hammers, stone points, working areas, and 12 stone ovens. Considering the camp’s industrial nature, it was surprising to find a girl buried between the rocks. Interred around 3,200 years ago, the grave was bare except for the skeleton. Aged 12–15, she showed no signs of disease or bone trauma. The cause of her death remains unclear, but she’s a priceless window into the earliest community of corn farmers in the Greater Southwest. The burial occurred around 1360 BC, which falls into the same period as a nearby hilltop settlement called Cerro Juanaquena. The community successfully introduced agriculture in the desert, including the earliest maize in Chihuahua. No human remains were found at the settlement, which makes this teenager extra special. Further research on her remains will hopefully reveal the lost history of these first farmers.

9 The Vindolanda Footprint

The permanent footprint or handprint of a child pressed into a slab of concrete is a scene that is very familiar today. Some kids even draw their names and the date in freshly made slabs. While it’s not always such a big deal to mess with affordable cement in modern times, archaeologists believe that one teenager transgressed onto pricier material and likely wasn’t popular with the adults because of it. Between AD 160–180, an adolescent pressed his or her foot into a tile of clay, leaving their toes and sole to be preserved for posterity. Researchers working at the Roman fort of Vindolanda, where the artifact was found, aren’t sure if the teenager felt a little naughty or whether the person accidentally walked onto the tile before it had a chance to set. The excavations, which ended in 2015, didn’t find any more such imprints. This makes it likely that the youngster did it accidentally or received such a scolding that he or she didn’t even think of trying it a second time.

8 The Starving Boy

In 2011, a skull was found by cave explorers outside Ballyvaughan village in Ireland. It wasn’t new, prompting archaeologists rather than the police to descend upon the cave. They pieced together a tragic story. At first, the size of the skeleton made everyone think it was a boy around age eight. But dental analysis showed that he was a severely stunted 14- to 16-year-old. When experts examined the bones, it became clear that he had lived a hard life. For most of his existence, the adolescent had suffered from such starvation and probably illness that it stopped his skeleton from growing at least once a year. He died between 1520 and 1670. During that time, the area buckled under two decades of war, sickness, famine, and death on a large scale. Having already gone through a miserable life, the boy also suffered a lonely death. There’s no indication that he was murdered or even buried in the niche where he was found in a huddled position. What he was doing in the area will never be known. But the teen likely fell through an opening in the cave roof, crawled into the space, and died.

7 Italy’s Witch Girls

In medieval Italy, a sick girl received a peculiar burial. Respect for the deceased was so far removed from the details that archaeologists began to suspect they were looking at the victim of a witch hunt. She was burned and roughly dumped before the gravesite was fortified with hefty stone blocks, almost as if to prevent the dead girl from rising. During her short lifetime of 15–17 years, she grew no taller than 145 centimeters (4’9″). She also suffered from crippling iron-deficiency anemia, weak enamel from childhood malnutrition, and possibly scurvy. Unnatural paleness and fainting spells could have led a superstitious community to view her symptoms as witch-identifying signs. It’s not known whether she was burned alive. But analysis showed that soft tissues were present at the time, indicating that it happened shortly before or after death. This is not the first time that an ancient “witch burial” featuring a sick girl was found at San Calocero. On an earlier occasion, a 13-year-old female with scurvy was found buried facedown in a probable attempt to stop her from escaping the grave.

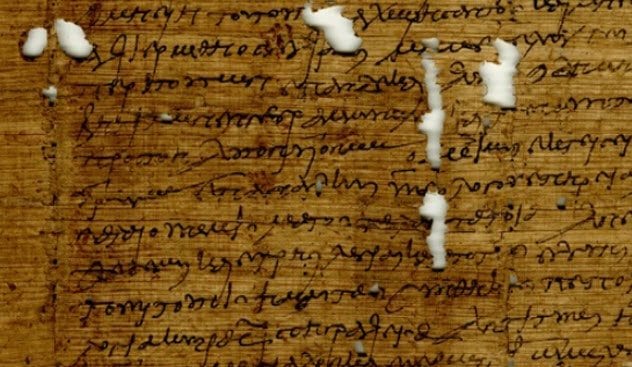

6 They Threw Matches

Winning in ancient Greece was everything. Getting paid was just as nice. A highly unusual Greek document was recently deciphered as an agreement to fix a wrestling match. The contestants were two teenage boys named Nicantinous and Demetrius. Drawn up in the year 267, the contract dictates that Nicantinous must win the match, something his father was willing to pay Demetrius for. The prize was to emerge as the winner of an elite wrestling tournament in Egypt. Demetrius agreed. But he stipulated that the bribe still had to be paid if the referee realized the event was rigged. On the other hand, Demetrius had to pay up if he somehow won the game. Even though match fixing was said to be rife in the ancient sport arena, this is the first direct evidence to come to light. It’s a bit odd to draw up a legal contract for an illegal activity, though. Neither party could exactly drag the other before a judge should the agreement be broken.

5 Given To The Gods

Evidence of another Greek rumor, this time of child sacrifice, was found at Mount Lykaion. The site was once dedicated to the god Zeus. Since 2007, one area that received particular attention was a mammoth altar. Excavations turned up vessels, figurines, coins, and a massive amount of burned goat and sheep remains. There’s no doubt that this was an altar used for sacrifice. Needless to say, it raised a few eyebrows when the 3,000-year-old skeleton of an adolescent male became the structure’s next find. Ancient sources support the notion that the boy was included in the offerings. Several state that human sacrifice was performed at the very altar on Mount Lykaion. The unfortunate boy is missing the upper part of his skull, but the rest of his frame represents the first human bones to be retrieved from the entire sanctuary. The chance that the young man was killed to honor Zeus is highly likely. If he had died naturally, one would expect to find him in a graveyard, not at an altar where animal sacrifices were also buried.

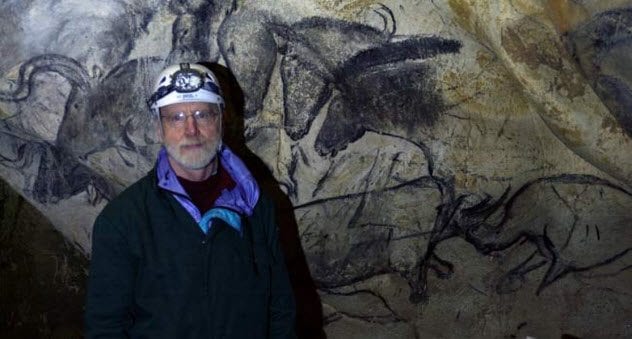

4 Graffiti Artists

The Pleistocene Epoch saw its share of teenage graffiti artists, too. Similar to modern times, most of them were teenage males. Thousands of cave paintings created from 10,000 to 35,000 years ago were studied to determine the dimensions of each artist’s hand. These were then compared to 1,000 photocopies of volunteers’ hands from both genders and various ages. This enabled researchers to accurately identify the physical makeup of each ancient painter. They found that everybody contributed. Grown men, women, and girls also created cave art. However, male adolescents outstripped them all. Their work was a far cry from the detailed, epic animal scenes or shamanistic visions that leave visitors in awe today. Similar to modern teens drawing graphic battle scenes, pornographic images, and cars, the Pleistocene gang painted sloppy hunting scenes that were high on gore and gruesome details. In addition, they drew animals of power such as cave bears and lions. Perhaps unsurprisingly, they spent a lot of time creating genitalia and their dream female nudes.

3 Roman Camp Refuge

In 2011, archaeologists found the grave of a young woman with a crushed skull in Kent, England. Ancient heads get smashed for a variety of reasons. It’s nothing new, but the horrors preceding her execution made this a particularly tragic case. Aged around 16–20, she was likely a local Briton kidnapped by Roman soldiers during their second sacking of Britain. While investigating a Roman camp, archaeologists opened ancient refuse ditches. Inside them were horse tack and ceramics dating to around AD 50. The soldiers buried the unwanted gear after they conquered the Kent area and moved on to confront the next population. Discarded amid the military refuse was the girl. Her exact story isn’t certain, but it appears that she was kept at the camp for as long as the soldiers stayed. When they became ready to move on, they disposed of their broken equipment—and her. The healthy girl probably died while kneeling, her skull shattered by the brutal blow of a sword. Tipped into a shallow trench, she was buried facedown where she fell. The discovery challenges an old belief that Britain’s homegrown folks flourished under Roman rule.

2 Naia

Naia was the name given to a teenage mother who fell to her death in the Yucatan Peninsula, Mexico. The 30-meter (100 ft) plunge broke her pelvis, and nearly 13,000 years passed before divers found her bones in the now-submerged cave in 2007. A study of her skeleton provided interesting details about her life and the origins of Native Americans. Her DNA showed that one Asian group of emigrants were the ancestors to both modern Native Americans and the first American settlers. Naia herself was a 15- to 17-year-old teen who knew hardship. Her arms weren’t well-developed, which common tasks such as grinding and carrying loads would have corrected. For some reason, she didn’t regularly perform such chores. Instead, she had the strongly muscled legs of somebody who walked great distances. A lifetime of malnutrition caused tooth decay, halted growth, and led to a stick-thin figure. The upper arm bone was as thick as a man’s little finger. The girl also had osteoporosis. This was likely because she became pregnant so young. The healing of labor scars on her pelvis means that she had a baby a long time before she died.

1 The Cannibal Colony

Five historical accounts mar the image of Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in Virginia. They describe how the people of Jamestown cannibalized each other during winter 1609. Many chose not to believe it, but a nauseating discovery in 2012 revealed the truth. Inside a cellar used to store the colony’s trash was a shinbone and skull. They belonged to the same 14-year-old girl, whom the team nicknamed “Jane.” A forensic anthropologist verified their darkest suspicions. Horrifyingly, Jane had been butchered after death. Multiple hacking wounds to her head show the attempts of a hesitant cannibal who went after the facial muscles, tongue, brain, and throat. The weapon was identified as a cleaver. Dental and skeletal analysis showed that Jane came from the southern coast of England and that her diet was European. This meant that she arrived at the wrong time—in 1609—when the winter and hostilities with indigenous tribes killed 80 percent of Jamestown’s citizens. How many were consumed by their starving neighbors remains unknown. But so far, Jane is the only proof of cannibalism in a European colony. Read More: Facebook Smashwords HubPages