Modern medicine has advanced considerably in recent times, and our understanding of pathology has never been better. However, history shows that mistakes are all too often made in the pursuit of scientific achievement. When it came to disease, even some of the most revered thinkers got it spectacularly wrong. As you might expect, such theories led to some rather baffling treatments. From lobotomies to bloodletting, scientists throughout the ages have offered some fairly crackpot therapies. The more you know about the history of medicine, the more you question the legitimacy of current theories. What else have we gotten wrong? What more is there to discover? Only time will tell.

10 Female Hysteria

Scientists once used pseudoscience as a means of correcting hysteria in women. The theory dates back to ancient Egypt. Many great thinkers imagined that hysteria was brought about by the position of the uterus (aka “the wandering womb”). The word “hysteria” is derived from the Latin hystericus (“of the womb”). Smelly substances were often placed near the vagina to correct the problem. The ancient Greek physician Aretaeus thought the womb was repelled and attracted to different fragrances. The scent of the substance used depended on whether the uterus was high or low. The medical fraternity’s understanding of hysteria turned stranger still. According to Greek mythology, the priest Melampus was said to have rid Argo’s virgins of their strange behavior. The daughters of King Proetus went mad and hallucinated that they were wandering cows. Melampus cured the women with roots of the flower hellebore and instructed them to make love to virile men. And so the notion of a “melancholy uterus” came to pass. Prominent thinkers, like Plato and Hippocrates, believed the female uterus had its own moods. Lack of sex and reproduction were thought to make the uterus sad. An unhappy uterus, argued Hippocrates, was ultimately caused by a buildup of poisonous humors. These humors then migrated to other parts of the body and caused disease. Similar theories persisted from ancient Rome onward.[1] According to US scholar Rachel Maines, theories surrounding hysteria led to the invention of the vibrator. In the 19th century, doctors were tasked with pleasuring women into a state of normality. It is said that doctors, bored with giving manual hand jobs, passed the responsibility on to midwives. (Other scholars disagree with Maines’s hypothesis.) The electromechanical vibrator was originally invented in the late 1800s to massage muscles. Medical doctors decided it would be quicker to use the device to give women “hysterical paroxysms” (i.e., orgasms). Treatment times were slashed from around an hour to just 10 minutes.

9 Trepanning And Evil Spirits

Today, the practice of drilling a hole in one’s head to treat mental health problems is a tough sell. But that was not always the case. From Neolithic times to ancient Greece, numerous civilizations used a procedure called trepanation to combat disease. Trepanation involves making a hole in the human skull to remedy some perceived ailment. During Paleolithic times, primitive tribes used trepanation to expel evil spirits from the body. In reality, the symptoms witnessed probably stemmed from mental illness. Skull fragments from the operation were highly sought after. Shamans would fashion amulets from the fragments in the hopes of fending off demonic possession. The warring tribes of South America put the procedure to slightly better use. They used trepanation to treat traumatic head injuries. Today, modern surgeons use a refined form of trepanation to alleviate intracranial pressure. So perhaps there was some method to their madness. Even now, a few brave souls use trepanning techniques to alter the flow of blood and cerebrospinal fluid in their heads. (N.B.: Do not try this at home unless you enjoyed the ending to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest.) Amanda Feilding, founder of the Beckley Foundation, performed self-trepanation in the early 1970s. She believes that “stagnant pools” of toxins contribute to diseases like Alzheimer’s. Feilding ran for parliament in the UK twice on a platform of providing “Trepanation for the National Health.” She received few votes.[2]

8 The Elixir Of Life

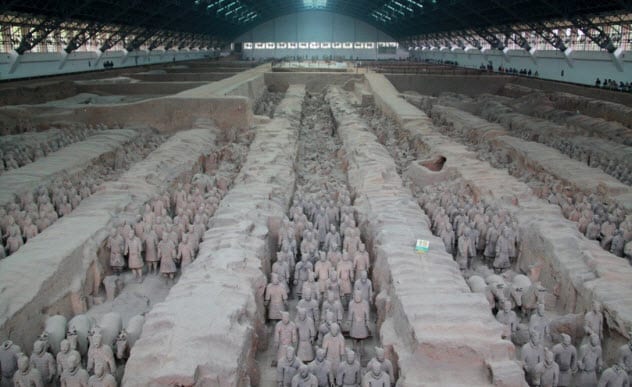

They say two things are certain in life: death and taxes. But it seems that the elites of ancient China were obsessed with avoiding the former. In a bid to find the elusive “elixir of life,” they put their faith in alchemists. Over 2,000 years ago, the very first emperor of unified China, Qin Shi Huang, ordered his men to find a potion that would make him immortal.[3] In what can only be described as an epic miscalculation, alchemists gave the emperor his elixir: mercury. As we now know, mercury only serves to bring about the recipient’s speedy demise. Historians believe the emperor was poisoned after consuming an unhealthy dose of mercury sulfide. He died at the not-so-immortal age of 49. Despite this obvious failure, alchemists continued their work. Many of them died toiling over their elixirs. Before his passing, Qin Shi Huang ordered the creation of his Terracotta Army. These inanimate warriors were placed in the emperor’s enormous burial chamber to protect him in the afterlife. Ironically, archaeologists think Qin Shi Huang’s tomb is surrounded by a river of mercury. Qin Shi Huang was not the only emperor to succumb to the temptation of quicksilver. Emperor Xuanzong of Tang was given an elixir derived from a mercury ore (cinnabar). He developed classic symptoms of mercury poisoning, including itching, muscle weakness, and paranoia. The alchemists argued that these symptoms were a mere blip on the road to immortality. Of course, the emperor died shortly after. A number of Xuanzong’s predecessors died taking similar elixirs, including emperors Muzong and Wuzong. Emperor Muzong suspected something was up, so he made his alchemists consume their own poisonous concoctions. Muzong’s wisdom did not last long. He, too, became obsessed with elixirs and poisoned himself.

7 Miasma Theory

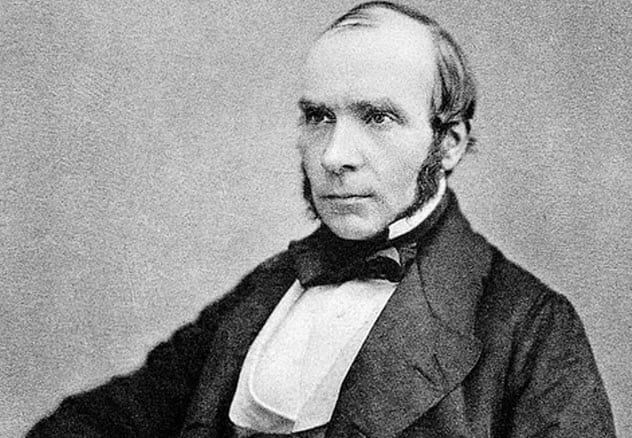

The miasma theory was proposed to explain the spread of disease. Before the germ theory came to pass, scientists thought that atmospheric impurities (“miasmata”) were the primary cause of disease. Plague doctors were illustrative of this theory in action. These frightening characters wore beak-shaped masks that were designed to keep foul-smelling miasmata away. The masks were packed with aromatic herbs to stop doctors from inhaling “bad air.” In Victorian England, Edwin Chadwick put forward the miasma theory to explain London’s cholera epidemics. Meanwhile, Florence Nightingale argued that outbreaks of measles, smallpox, and scarlet fever were caused by building houses too close to smelly drains. An anesthetist called John Snow refuted the miasma theory. Snow said that cholera was transmitted via polluted water, not bad air. This was a controversial hypothesis for the time.[4] Snow observed that certain parts of London were more likely to experience cholera outbreaks than others. He realized that some of the local water companies filtered and purified their water, while others did not. All the companies took their water from the Thames—a swirling cesspit of refuse, effluent, and general despair. (Some things never change.) Regions with high levels of cholera often received unpurified water from especially dirty parts of the Thames. Snow also discovered a link between the spread of waterborne diseases and the city’s inadequate sewage system. One major outbreak was caused by a cholera-riddled diaper that had been dumped in a leaky cesspit. The disease took hold when water from the cesspit contaminated a nearby water pump. In 1861, Louis Pasteur’s germ theory proved that Snow was correct. The discovery of the bacterium Vibrio cholerae was the final piece of the puzzle. The miasma theory, which dated back to the time of Hippocrates, was finally put out to pasture.

6 Tooth-worm

Dental caries are no joke. This was especially true in Babylonian times when the Legend of the Tooth-worm existed. Thereafter, a number of ancient civilizations thought that wriggly worms were responsible for cavity-related pain. The theory goes that a nasty worm would bury itself in the tooth. Its wild movements inflicted great pain on the sufferer. Only once the worm tired and ceased its thrashing would the pain subside. Some civilizations thought that the creature was actually a demon taking on the guise of a worm. Fumigations and extractions were popular treatments for tooth-worm. Scribonius Largus, the physician to the Roman emperor Claudius, performed fumigations with henbane seeds. It was said that the resultant fumes would repulse the pest. During the 17th century, a number of charlatans conned patients into thinking they had tooth-worm. The practitioners would only pretend to extract worms. In reality, they were simply removing pieces of lute string.[5] Roman philosopher Pliny the Elder is worth a brief mention. Pliny’s cure for toothache involved capturing a frog by moonlight, spitting in its mouth, and saying, “Frog, go, and take my toothache with thee!” In 1728, Pierre Fauchard published a two-volume book, The Surgical Dentist. Described as the “father of modern dentistry,” Fauchard debunked the theory of tooth-worm and recommended that patients reduce their sugar intake.

5 Ulcers And Stress

Until recently, practitioners and researchers were united in their belief that ulcers were caused by stress and excess stomach acid. Scientists who were skeptical of this entrenched theory were the subject of ridicule. So, in 1984, Barry Marshall set out to make a point. The Australian gastroenterologist was convinced that ulcers were the result of a bacterium called Helicobacter pylori. He was so convinced that he started experimenting on himself. His colleague cooked up a delicious broth of H. pylori, which Marshall then drank. Now a miserable vomit-sprinkler, Marshall was diagnosed with acute gastritis. He cured himself with a simple course of antibiotics. The theory behind stress-induced ulcers was beginning to crumble.[6] However, Marshall and his colleagues faced considerable pushback from the medical-industrial complex. A number of big drug companies were worried that antibiotics would make their products redundant. “Because the makers of H2 blockers funded much of the ulcer research at the time, all they had to do was ignore the Helicobacter discovery,” explained Marshall. For the longest time, the idea that bacteria could survive in such an acidic environment was laughable. But scientists soon discovered that Helicobacter could effectively neutralize the acid around it. Researchers now think that 80 percent of gastric ulcers are caused by the bacterium. Barry Marshall and colleague Robin Warren won a Nobel Prize for proving their peers totally wrong.

4 Corpse Medicine

Corpse medicine was the practice of using human corpses to treat illness. The part of the body consumed was dependent upon the ailment. “Like cures like,” argued the homeopaths. Therefore, nosebleeds and epilepsy were often treated with bits of skull, while superficial wounds were wrapped in fat-soaked bandages. Europe’s rich and famous were pigging out on human bodies during the 16th and 17th centuries. The continent was rife with cannibalistic gravediggers looking for a quick buck. Egyptian tombs were looted of their mummified inhabitants and used to treat bruises and bleeds. Even royalty was at it. England’s King Charles II was partial to a little alcohol and ground skull (aka “The King’s Drops”). The king would tootle off to his own laboratory and brew up a batch himself.[7] Another form of corpse medicine was seen in 19th-century Denmark. Public executions were attended by blood-lusting spectators, many of whom brought their own cups. In 1823, Hans Christian Andersen described witnessing a man feed the blood of an executed felon to a child. The blood was used as a treatment for epilepsy. Blood was referred to as the “elixir of life” throughout the Middle Ages (marginally better than mercury), and virgin blood was used to cure leprosy. This “medical vampirism” dates back to ancient Rome. Numerous civilizations thought that human blood carried the soul. Drinking blood, they theorized, could stave off illness and afford new strength. It was this mystical belief that compelled the Romans to drink the blood of gladiators killed in the arena.

3 The Four Humors

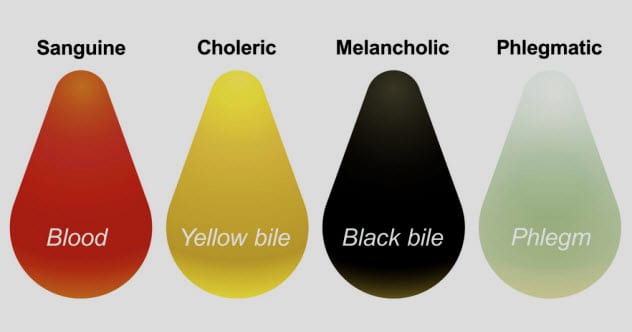

Knowledge of anatomy and medicine soared under the physicians of ancient Greece. Dissections and vivisections provided doctors with fresh insight into the body’s inner workings. Galen found that the brain controlled movement via nerves. Herophilus distinguished between veins and arteries. A number of prominent philosophers drew a connection between disease and the environment. And a biological trigger of disease replaced the supernatural. However, one deeply flawed theory went uncontested: the four humors. Ancient Greek medicine was heavily influenced by Hippocrates. His theory on humoralism supposed that the body was made up of four fluids: blood, phlegm, black bile, and yellow bile. An imbalance in these fluids, or humors, would lead to disease. The four humors were also associated with an individual’s mental state. For example, a patient was melancholic if he had too much black bile.[8] But where did the idea of these humors come from? Well, the ancient Greeks were likely pouring blood samples into glass containers and leaving them to coagulate. After some time, this sample would separate into four distinct layers: red, white, black, and yellow. This is perhaps what they thought of as humors. However, the Greeks may have taken inspiration from the four elements: earth, air, fire, and water. It was also widely accepted that these humors were somehow connected to the four seasons and planetary alignment. Changes to diet and lifestyle were often recommended to redress the balance. The Greek physician Galen was a proponent of bloodletting to get rid of excess blood—what he considered to be the dominant humor. Bloodletting continued under the barber-surgeons of medieval Europe who thought the practice could cure smallpox and epilepsy. Humoralism persisted throughout the West for thousands of years. Historians suspect that George Washington’s faith in bloodletting may have contributed to his demise in 1799.

2 Urine Therapy

Simply put, urine therapy involves using urine to combat disease. Those in support of the practice extol its apparent healing qualities. Books about urine therapy wax lyrical about the “elixir of life,” “the golden fountain,” and “liquid gold.” While most qualified doctors view urine as a waste product, urine connoisseurs claim that the liquid is a distilled product of the blood (aka “gold of the blood”). Urine has been used throughout history with alarming frequency. Thomas Vicary, Henry VIII’s surgeon, advised cleaning battle wounds with urine. The 17th-century chemist Robert Boyle instructed patients to drink “a moderate draught of their own urine” in the morning. On the recommendation of George Thomson, urine was used to combat the deadly bacterium responsible for the Great Plague.[9] A quick perusal of the Internet reveals that urine therapy is something people still do today. Hundreds of thousands of people in China are said to drink urine. A surprising number of athletes have also resorted to guzzling down their own juices, including MMA fighter Luke Cummo and boxer Juan Manuel Marquez. Madonna famously told David Letterman that urine was a cure for athlete’s foot. Some desperate teens have taken to slapping urine on their pustulous faces, while others are brewing up their own urine-based teeth whiteners. For obvious reasons, there remains little research on many types of urine therapy. But doctors are adamant that drinking pee is a bad idea. The practice has no health benefits and can lead to dehydration. Cleaning your wounds with urine is also a bad idea. New research shows that urine is not sterile, as was once thought to be the case.

1 Powder Of Sympathy

Sir Kenelm Digby was a man of science, philosophy, and reason. But, like many of his 17th-century contemporaries, Digby had a keen interest in alchemy and astrology. The Englishman came up with the strange notion that applying treatments to the weapon that caused an injury would heal the wound itself. This miracle cure was called the “powder of sympathy.” Digby’s theory was delivered to top academics at the University of Montpellier. The speech lasted two hours and boasted of endorsements from King James. Digby’s belief in the treatment came after experimenting on his friend James Howell. The writer was wounded while trying to stop a duel in England. In this instance, the powder of sympathy was tested on Howell’s blood-soaked bandage. The bandage was then removed and kept separate from the wound. The treatment reportedly gave Howell “a pleasing sense of freshnesse” and a new lease on life. However, today’s scientists know better. His recovery was likely the result of good fortune and the placebo effect. According to Digby, a Carmelite monk taught him the weapon salve. The potion was supposed to work on the basis of “sympathetic magic.” Proponents argued that a weapon would form some kind of connection to the human body after drawing blood. Digby and his colleagues believed that atoms of the lotion were attracted to the wound via some form of magnetism. The powder of sympathy garnered considerable attention. There were 29 editions of Digby’s book, A Late Discourse . . . Touching the Cure of Wounds by the Powder of Sympathy. The potion was sold in many apothecaries throughout 17th-century Europe. Even the likes of John Locke and Thomas Sydenham lauded the bizarre treatment. Digby’s love for the supernatural did not end there. He also had a keen interest in palingenesis, a form of “biological rebirth.” He hoped that the technique would resurrect life from the crystallized ashes of plants and animals. Some scholars suggested that Digby’s attempts at resurrection were related to an obsession he had with his dead wife, Venetia. Rumor circulated that Digby had accidentally killed Venetia by giving her large quantities of “viper wine.”[10]